In the days before my daughter's birth, I was reading about the fear of death. Ernest Becker won a Pulitzer Prize in 1974 for his book The Denial of Death. In it, he argues that our lives are structured around the fear of death. In the posthumously published follow-up, Escape from Evil, Becker writes:

"Man wants to persevere as does any animal…but man is cursed with a burden no animal has to bear: he is conscious that his own end is inevitable."

For Becker, human culture is really a series of attempts to avoid or transcend the reality of death. We follow charismatic leaders in the hope of becoming part of something greater. We have children in the hope that something of us will last beyond the span of one lifetime. We collude to marginalise pensioners and prisoners and any other reminders of our frailty, hiding them away so we can briefly pretend at immortality.

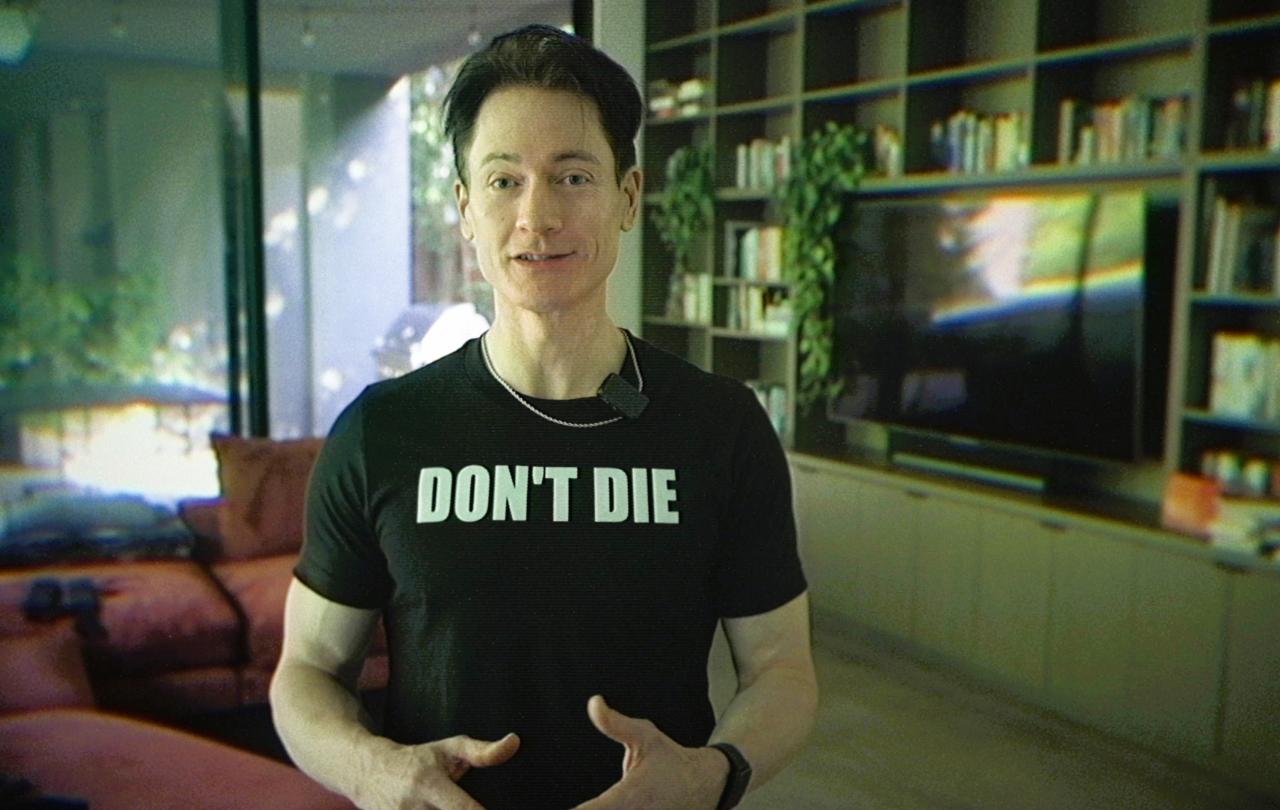

Last week I thought of Becker when I watched Don’t Die: The Man Who Wants to Live Forever on Netflix. The documentary follows Bryan Johnson, who made his millions in tech and is now going to extremes to undo the impact of ageing on his body. An exacting routine of dieting, sleep, fitness and medication is augmented by riskier interventions, such as experimental gene therapies.

As Johnson tells it, his past struggles with mental ill health and suicidal ideation led him to pursue a life less reliant on his mind. He seeks instead to listen to what his organs tell him they need via algorithms and diagnostics: fallible humanity corrected by data.

Johnson is resolute that it is not fear of death that drives the enterprise but a desire to live, particularly to live as long as possible with his son. One of the documentary’s strangest and most touching scenes is an inter-generational plasma transfer. There is evidence that plasma from a younger donor can have a de-ageing effect on a recipients' organs. So, Bryan decides to give his dad some of his plasma and his son gives him some plasma. Each of the three men, we learn, have experienced isolation after leaving Mormonism. The transfer becomes a kind of founding of a family outside the faith they have each rejected and been rejected by.

Johnson’s pursuit of longevity now plays an equivalent role in his life to that faith– not just as a source of belief and human purpose, but of human connection. The documentary ends with a montage of "Don't Die" communities around the world hiking and dancing and celebrating life together.

In the months after my daughter's birth, I recognised something of what Becker names. Here is someone who will outlast me, something of me will transcend the limits of my life. And here is someone who reminds me of those limits. Here is this great gift and joy who will sit in the front row at my funeral: the embodiment of life’s goodness a witness to its end.

Are we wrong to fear death? If there was a way beyond it, shouldn't we give up everything to find it?

There is more going on in Bryan Johnson and the wider de-ageing movement than Becker's analysis would perhaps allow. Fear of death is not the only story here. When is it ever, really? Fear only makes sense alongside—and in light of— goodness, life, gift. To fear loss, you must have something to lose.

And yet, the story Becker tells about culture does seem to ring truer in the years since his death. As technology improves, death's denial becomes more convenient. As the natural world degrades, it becomes more compelling. And as wealthy men become wealthier still, their denial on behalf of us all becomes ever more creative.

And who can blame us—any of us? Are we wrong to fear death? If there was a way beyond it, shouldn't we give up everything to find it?

This Wednesday, Ash Wednesday, marks the beginning of Lent, the Christian season of reflection and self-denial. On Wednesday, I will receive an ash cross, and as I draw that same cross on forehead after forehead, I will repeat these words:

"Remember you are dust and to dust you shall return,

turn away from Sin and be faithful to Christ."

I will hear the invitation, in my voice and not my own, to give up the futile theatrics of a deathless life. I will pray for the strength to live what I have spoken. I will say goodbye to those who I marked, each of us now a signpost to our shared mortality. And then I will go home to yoghurty hands, bathtime songs and giggles at the funny smudge on my face.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief

Find out more and sign up