Christians have an odd belief that their little lives are somehow joined up to the very life of God.

And not just God ‘generally’ or in a spiritual sense, but that they are interconnected to the life of someone who lived 2,000 years ago. That they have his ‘spirit.’ That he lives in them, and they in him.

They built cathedrals on this foundation. They faced lions for this claim. They reoriented their sense of time. They believed that in dying, they would meet him - a person - all the sooner, face to face. One of the first early Christian bishops begged his congregation to not try and stop him from entering the gladiatorial arena and going not to his death (as one would think) but, as he eloquently urged, to his birth.

These cultural relics grew from the soil of a deep conviction

It is in this context alone that we can understand something of the significance of things like Easter, Christmas, Michaelmas, Whitsuntide, and all the other festivals that shape our heritage. These cultural relics grew from the soil of a deep conviction that humans could keep step with the life of God, because he had kept step with them, in their skin. These were not celebrations of an ossified past, but of a living present - celebrating what had and was happening to them, in them.

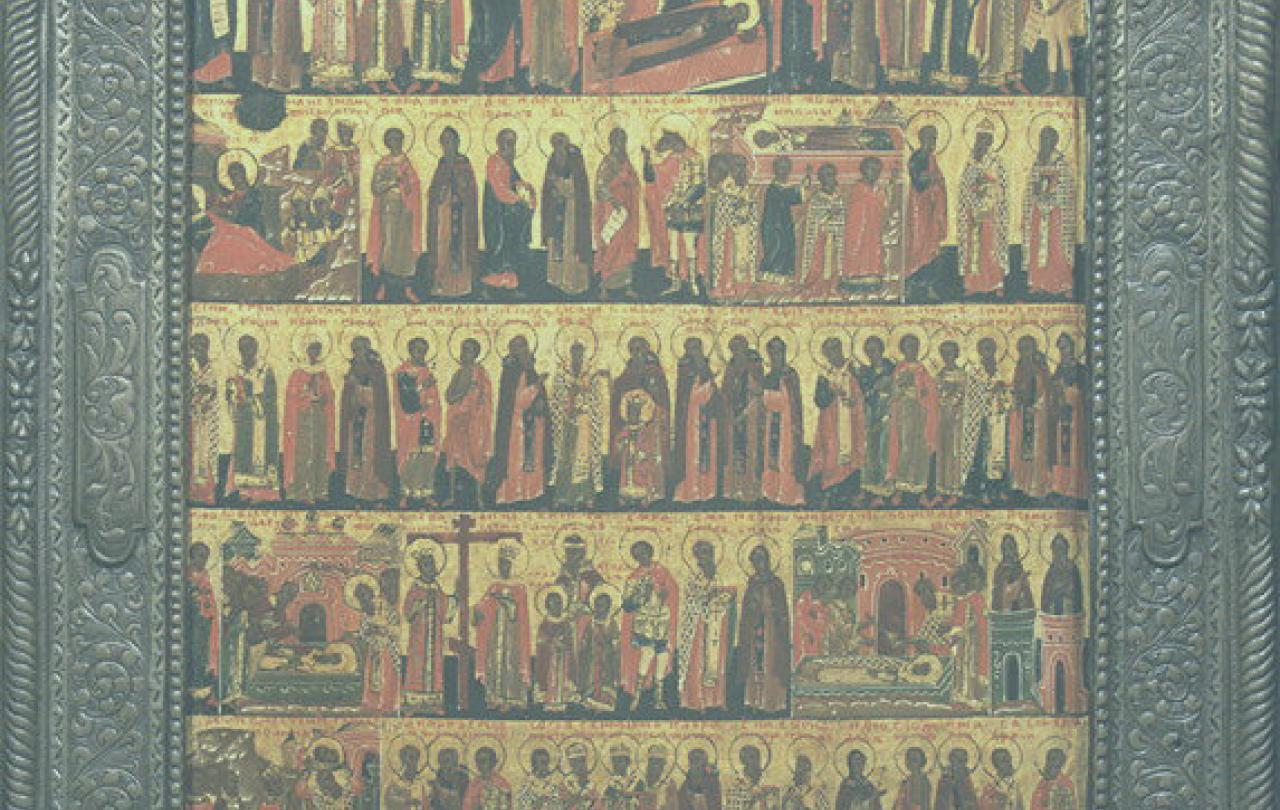

And so these early preachers and teachers told their congregations that Christmas is not Jesus' birth, but their birth. That through these festivals, they were not remembering his past but the mystery that their present was forever bound with his past and future. And because they had died and been raised with him in baptism (an ongoing reality that was celebrated both annually at Easter, and weekly on Sunday which was called a ’little Easter‘) they were to now keep in step with him by caring for the poor (St Nicholas), feeding the hungry (St Thecla), preaching to the birds (St Francis), reconciling towns (St Martin), and averting war (St Leo - who met with Attila the Hun). There were goodies and baddies. There were odd ducks and beautiful virgins. Recluses and repentant sinners. They were an odd, but galvanized lot around the history of a man from Palestine, in whose shoes they sought to walk and to whom they believed they were mystically united.

Strange. But perhaps no odder than our own times, with our own calendar with our important festivals galvanizing our sense of nationalism, or our identity as consumers. The fiscal year. The academic year. The consumer cycle. We need something to hallow our days.

I am caught up in a transcendent pattern that offers me an escape from the narrowness of my echo-chambers, my appetites, my loneliness

So what are we to do with this ancient calendar, filled with its colourful saints and high days and holy fare? I don't know about you, but I need its naive defiance that my life, lived in my ordinary home on my ordinary street in my ordinary family, is somehow connected to something much larger than myself. That year after year I am caught up in a transcendent pattern that offers me an escape from the narrowness of my echo-chambers, my appetites, my loneliness. That my suffering need not destroy me. That my career (or its 24/7 maintenance due to the digital revolution) is not worth the price of my soul. This calendar provided our forebears with an opportunity for an inner journey, an acknowledgement of our hunger for life beyond the material. And perhaps it is time that we listened to their wisdom, if only by lighting a candle or eating a goose on Michaelmas day. Or maybe, just maybe, we might attend to that inner call that asks us how to hallow our lives, and welcome the one who hallows all time.