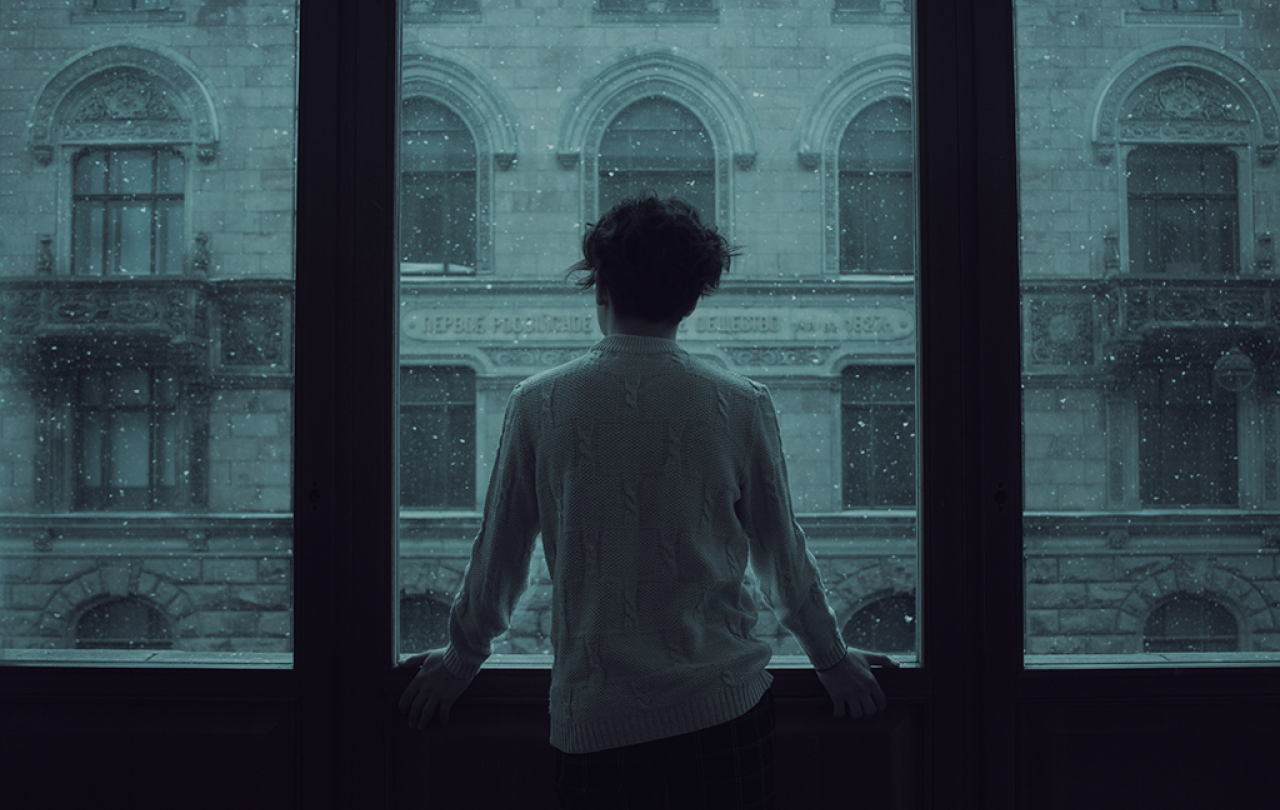

My midlife crisis began with crying. Alone. In the car. In the study surrounded by books. Curled up on the bathroom floor. Waves of sadness crashed over me, and I couldn’t hold them back. So sudden and inexplicable was this lapse into grief that I felt the need to keep it to myself. It was shameful. It took a month before I finally told anyone and even then, my hand was forced by bursting into tears in front of them. They wondered if it was hormonal. Maybe I was eating badly or sitting still too much. But I knew the sadness had content.

I was slowly being crushed by the feeling that I had failed to be, or missed the opportunity to become, the man I was supposed to be.

It is difficult to make sense of such sadness though. It doesn’t come labelled with its own meaning. It fails to announce itself. It doesn’t ride into our consciousness on a unicycle waving a sign that reads: you are now sad about getting old and feeling like you have failed as a man. It takes a bit of detective work to find out what it all means. But in the end, I had to acknowledge that I was slowly being crushed by the feeling that I had failed to be, or missed the opportunity to become, the man I was supposed to be. In the three areas of life that mattered most to me, family, work, and church, I was a failure. I knew that’s what I thought because my tear ducts started twitching whenever I said it aloud. Of course, I couldn’t get anyone to agree with me. It’s not a fact. It is a massive unrealistic incapacitating overgeneralisation. But apparently the poor twisted neurones of my emotional brain had failed to get that memo.

Every feeling of failure implies a vaguely defined sense of the success that could have been ours but has been lost. If I had failed as a man, what kind of man was I supposed to be? I came to realise that I had unintentionally imbibed a seductive model of masculinity that was ultimately unachievable. For want of a better term I came to call it the man-at-the-centre. The man-at-the-centre game is really easy to play. It is a simple rule of thumb for what any man should be. It works in any context you can think of, and goes like this…

What should a man be at work? He should be at the centre of a team of adoring colleagues.

What should a man be at home? He should be at the centre of an adoring wife and family.

What should a man be at church? He should be at the centre of an adoring congregation.

The man-at-the-centre game requires that every situation a man enters should immediately configure itself into a picture postcard in which he holds pride of place.

Obviously, this view defines masculinity entirely in terms of power. And not even the kind of power that makes any sense. Not the power to be wise, or brave, or generous, or fair, or honest, or loyal. But the power to force other people be exactly as we would like them to be. The insistence that social life is only acceptable if made to conform to our exact specifications. The man-at-the-centre equates masculinity with being in charge, and even the tiniest lapse in control as a failure to be a man, a surrendering of one’s right to exist as a male. Kierkegaard summed up despair in precisely these binary terms, the desire to be Caesar or nothing.

A one-way ticket to Blametown

I can’t be sure if this insight is true of ALL men, some men, or just me. Maybe it has nothing to do with masculinity at all. Perhaps I’m just describing my own narcissism. But either way, it’s embarrassing to admit that I even thought this. I don’t even know where this belief came from. It goes against everything I have stood for in support of women, and in collaboration with men. It is quite frankly a ridiculous thing to believe - and yet there I was, just as surprised as anyone else to find myself believing it. It turns out the old church billboard was right:

You are not what you think you are; but what you think, you are.

And I don’t really want to chalk it up to The Patriarchy. Whenever anyone starts on about The Patriarchy, I have the ominous feeling I’m about to be blamed for something. It reminds me how I used to feel when I worked in mental health services in the NHS.

Two- or three-times a year it seems the national media are obligated to run a story about the inadequacy of care for people with mental illness. Usually based on a report about people being let down. The catastrophic failure of care for young women with eating disorders, or young men with depression, or women on the autistic spectrum. The stories are heartbreaking, and everyone agrees that something must be done. As a lowly frontline worker, nobody blamed me, but I knew that in the weeks that followed I’d be subjected to something that felt very much like blame. No one said it was my fault, but the demands, the hours, the targets, the scrutiny, the bureaucracy would proliferate. None of it would solve the problem, but those who were trying to help would not go unpunished.

So, as a one-way ticket to Blametown, I’m not keen on too much talk about The Patriarchy. But when I consider my hardwired tendency to think of masculinity as the man-at-the-centre, and the despair that accompanies the failure to definitively accomplish this, am I not describing something a little bit like patriarchy? A social system that offers men such a restricted view of what it means to be male, that almost no one can be happy confining themselves to it. An invitation to inhabit a narrow bandwidth of conversations, interests, clothing, emotions and sitting positions so as not to score an own goal for the men’s team by betraying weakness. It’s not like any of this is working for anyone but, beyond exorcism, what can we possibly do about it?

The real Man-at-the-centre

It's not a huge surprise that this midlife crisis struck when it did. Every crisis has a context. Every breakthrough starts with a breakdown. Sometimes I feel like I invited it, because for the last five years I have been practicing contemplative prayer. Twice a day – on a good day – I hole up somewhere alone. Sometimes the study or the bedroom, my office at work, a bench in the park or a seat by the window. I pray in the same places I cry. The twenty-minute timer on my smart phone begins and ends with the sound of a monastery bell. And when it is set, I close my eyes and follow the simple rule of contemplative practice: lifting my heart to God with a humble stirring of love. And for twenty minutes that is all I do. In response to every distraction or entertaining thought, I turn from the noise of my mind back to being lovingly present to the mysterious Presence in the present moment.

Among all the well-intentioned ideas, initiatives, and apps that promise a solution, this is the only answer that has truly addressed the crisis of my own masculinity.

One of the central tenets of contemplative prayer is that when we make space for God like this, we not only meet Him, but we also meet ourselves. I don’t think my insight into needing to be the man-at-the-centre would have been available to me, if I hadn’t been practicing its polar opposite several times a day. In the discipline of contemplative prayer, we decentre the ego, we step over our self-absorption, we fill our consciousness with something that is not us. My experience of it is that when I turn to God with love, I find myself held in a vast field of loving attentiveness, infinitely greater than my own. And over time, this creeps into every corner of life, infecting every moment of contact with family, friends, colleagues, and students with the supreme joy of simply being there for that unique unrepeatable moment of their existence. Whether I am the man-at-the-centre of home, work or church becomes an irrelevance. What matters is not what these situations give to me, but what I can give to them.

This speaks to the supreme paradox at the heart of Christianity. One that is in constant danger of slipping through our fingers. If we grasp it too hard it crumbles in our hands. It stems from the fact that there is a man-at-the-centre of the Christian religion. Arguably the most famous man of all time. Depicted in icons, brushed into frescoes, melted in stained glass, moulded in sculpture, and portrayed on camera. His face appears everywhere, and if we are not careful, we may mistakenly assume that we are celebrating his fame – the greatest influencer ever born. But what makes Jesus the man-at-the-centre is not the ingenuity with which his publicity machine crowned him king of the hill, but the absolute giving of self that characterised his life. The real Man-at-the-centre is the radically de-centred Man.

Personally, I find there to be a seamless continuity between the Jesus I meet in scripture, and the Spirit that animates the life of prayer. Among all the well-intentioned ideas, initiatives, and apps that promise a solution, this is the only answer that has truly addressed the crisis of my own masculinity. Not a humiliation of masculine power, but a profound transforming and redirecting of it. It is the only thing I have yet found that can truly photosynthesise the carbon-dioxide of fear, rage and self-hatred that suffocates so many men, into the liberating oxygen of joyful loving strength that is their birthright.