From Johnny Cash to Kanye West, Rick Rubin has worked with some of the biggest names in music. Notably titled ‘the most important producer of the last 20 years’ by MTV, the famously bearded founder of Def Jam records has nine Grammy awards under his belt and is one of the most sought-after producers working today.

Written over the course of four years, a period that saw Rubin work with bands such as The Strokes and The Red Hot Chilli Peppers, The Creative Act: A Way of Being might promise a memoir yet assumes the form of something more like a self-help guide. Rubin distils what he has learned throughout his illustrious 40-year career into a series of short chapters that read somewhat like meditations, contemplating the meaning of art in general; how to make it well and why it matters to keep trying. While its dearth of personal anecdotes may be disappointing to fans hoping to gain insight into some of the producer’s many exploits, this book requires little to no contextual knowledge of Rubin’s life and work to enjoy.

“There was a version of the book three years ago,” Rubin told The Bookseller magazine last October. “The content was similar but the feeling of it... it did not feel like a call to action. It was beautiful, but it wasn’t inspirational.” If inspiring artists to create meaningful art is Rubin’s primary aim, suffice to say The Creative Act: A Way of Being largely succeeds.

Happily, this book is not just for musicians; for any working artist in search of practical guidance, Rubin offers encouragements and hands-on suggestions for how to cultivate discipline, maintain creative perspective and successfully finish work. His tips are, in many cases, refreshingly rudimentary. Set up a daily schedule of practice and stick to it. Level up your taste in the medium you are working in. Allow yourself to be distracted sometimes. Such instructions immediately reminded me of Oblique Strategies, Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s tarot-like deck of pithy creative prompts, conceived in 1975 as a work of art and designed to stimulate creativity. And the advice is sage. As an artist myself, I had barely gotten halfway through when my highlighter began to run out of ink.

Rubin’s thesis on art-making is full of self-aware contradiction. It is a serious matter, he says, but it’s also reliant on play. One should employ a rigorous schedule yet embrace rest and spontaneity. Practise your craft but be aware of the value in naivety;

‘often the most innovative ideas come from those who master the rules to such a degree that they can see past them or from those who never learned them at all’,

and remember that both years of artistic toil and a five-minute flash of inspiration can both produce a valuable result.

[It] does an excellent job of meeting the creative in their tiredness while celebrating their bravery.

It is this ability to understand and speak to the tensions faced by an overwhelming majority of artists that is a real strength of this book and a testament to Rubin’s experience as a producer. The creative process is rarely straightforward; success can be difficult to define and inspiration elusive. However, he admits, in the pursuit of great art ‘there are no shortcuts.’ The Creative Act: A Way of Being does an excellent job of meeting the creative in their tiredness while celebrating their bravery. It exists, at the end of the day, to remind them why it’s important to make art at all. I can corroborate this with my own experience: as a reader I brought all the baggage of any working artist. I felt understood and reassured, both by Rubin’s reverence for art-making and by his admission that art is rarely straightforward, and that artists can be hard to understand. This, for Rubin, is by no means an indictment. It’s part of the journey, and an important one at that.

Rubin’s reverence for the power of art and the significance of the artist is without question. This can sometimes, though, verge on the eulogising of unhealthy behaviour— an issue, I can’t help but feel, is endemic to the music industry at large.

'The great artists in history… are protective of their art in a way that is not always co-operative. Their needs as a creator come first. Often at the expense of their personal lives and relationships',

writes Rubin, excusing selfishness as a ‘childlike spirit’ to be aspired to. Surely, while singular focus is key, this doesn’t need to override a generosity of spirit, does it? Van Gogh certainly didn’t think so, famously writing:

‘there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people.’

There’s an evident undercurrent of divine inspiration woven throughout the book, too. Rubin acknowledges and explores the cosmic thread that runs through all things, the energy of which the artist both observes and channels through their work. The artist without this spiritual viewpoint, he posits, is at a crucial disadvantage. For Rubin, the spiritual world provides a crucial sense of wonder and a degree of open-mindedness rarely found within the confines of science. A dedication towards a deeper connection with and understanding of the ‘Source’ (the creative force of the universe) will inevitably merit a greater artistic encounter. Rubin therefore encourages artists to be disciplined in their spiritual practice in order to ‘build up the musculature of the psyche to more acutely tune in and receive from the divine’.

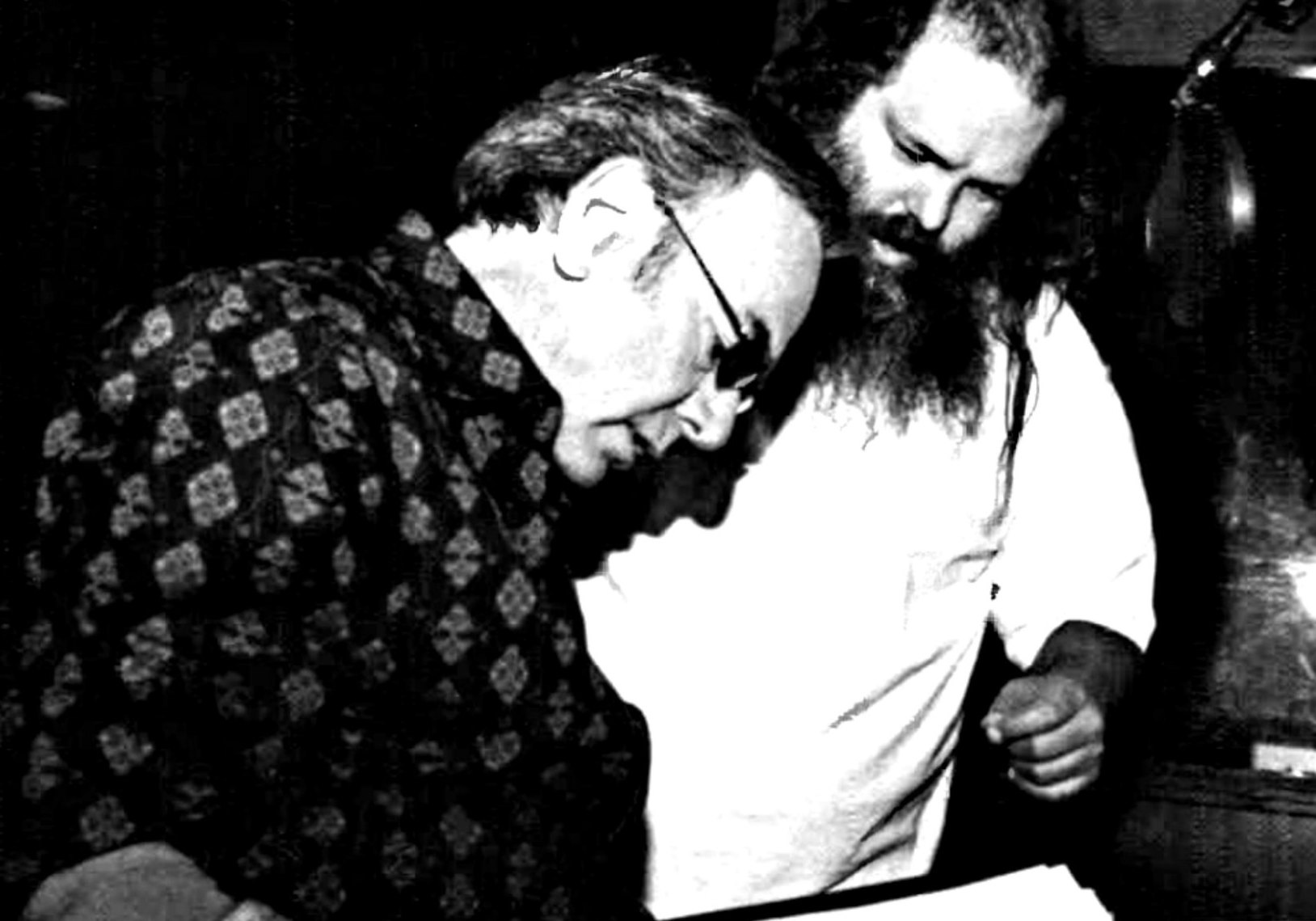

Rick Rubin with Neil Diamond, 2006. Photo by MusicLoverDiamond.

As a believer, of course I perceived Rubin’s ‘Source’ to be a metonym for the God of the Bible, and while occasionally Rubin’s universalism strays into abstraction— perhaps even cliché— there is genuine substance here; many of his spiritual encouragements overlap significantly with Christian teachings, for instance his appeal to artists to be ‘in’ currents of culture, not ‘of’ them, and the assertion that ‘it is better to follow the universe than those around you’. He admires the biblical attitudes of patience, discipline and child-likeness, and even quotes directly from the Bible’s book of Ecclesiastes, ‘for everything there is a season... ’, when illustrating the rhythms of nature.

Although it might be viewed as a simple guide to creative rules and rhythms, at the heart of this book the challenge is set.

You are either living as an artist, or you’re not. You are either adopting this way of being, or you aren’t.

Rubin takes no prisoners. The Creative Act: A Way of Being is an essential read for anyone looking to explore the importance of art or to remind themselves why they shouldn’t give up. For Rubin, a facilitator and a collaborator, the transformational powers of art are undeniable and artists themselves are almost magical creatures who need understanding and care. This book is both about, and for them.