My name is Stefani. I was a committed atheist for almost my entire life. I studied religion to try to figure out how to have spiritual fulfillment without God. I tried writing books on spirituality for agnostics and atheists, but I gave up because the answers were terrible. Two years after completing my PhD, I finally realised that that’s because the answer is God.

Today, I explain how and why I decided to walk into Christian faith.

Here at Seen and Unseen I am publishing a six-article series highlighting key turning points or realisations I made on my walk into faith. It tells my story, and it tells our story too. Read part 1 here.

Inhale…two, three, four… Exhale... two, three, four…. Inhale… two, three, four… exhale… two, three four…

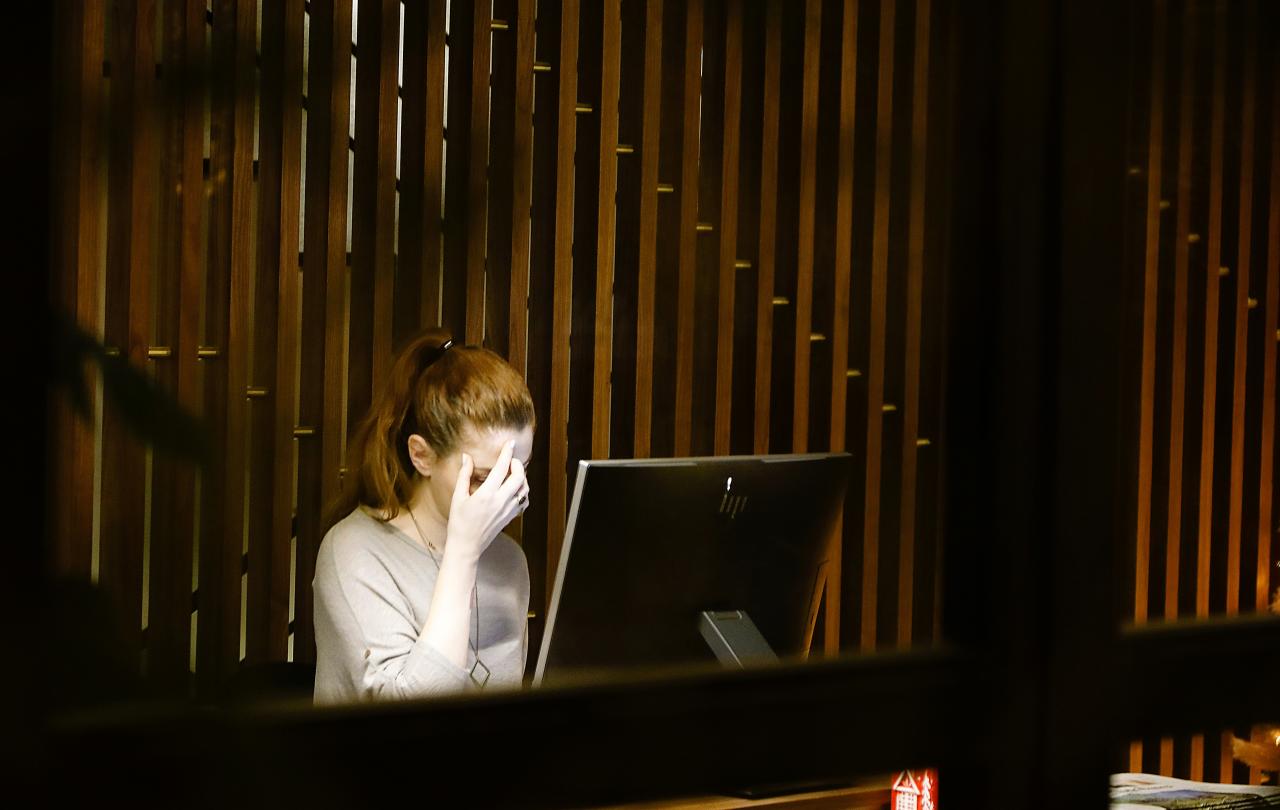

I was laying in bed, staring at the ceiling, doing breathing exercises trying to calm my body and mind. The clock on my bedside table flashed 3:59. I had a lecture on twentieth century French metaphysics to attend in four hours. But I couldn’t sleep.

Night time anxiety had been my habit for as long as I could remember. It all started when I was four years old and first asked myself what would it be like to be dead? while trying to fall asleep one night. Since then, my anxiety often started with normal, day-to-day worries (did I complete enough items on my to-do list today?). But they almost always spiraled into bigger concerns. I always found my way to questions like Is this really all there is?

I sighed and kept on with my breathing exercises. Inhale… two, three, four… exhale… two, three, four…

But then…

Then, I had an idea.

I blinked and sat up.

God might be there!, I thought to myself.

God might have been there all along!

I started to laugh, incredulous.

Here’s the two things I had just learned that made me finally wake up to this extraordinary possibility.

Interpretation is a choice

When I was an atheist, I often said that if God existed and wanted us to believe in Him, God would make it obvious. God would write something like 'Believe in Me!' in letters in the sky. God would give us indubitable evidence of His existence.

But interpretation is a matter of choice.

It’s like a story a man once told at my church. He was out walking in the woods at night. He said, God if you’re there, give me a sign! A shooting star went through the sky. He then shrugged and said to himself, oh, it’s a coincidence.

I had always told the story of my life as a string of coincidences. No matter how uncanny an event, I always assumed it was pure chance. But what if I had been ignoring the underlying narrative and purpose to things all along? God could be communicating with us and steering the course of our lives all the time, but if we never took the initiative to interpret our experiences with Him in them, we would never see Him.

The only way for me to assess God’s possible role in my life would be to start interpreting events as if God were the author. I wouldn’t have to get rid of my “pure coincidence” view. I would only have to add this new one. Then, I could compare the two.

Openness to evidence is a choice

The philosopher William James makes the extraordinary, underappreciated point that there are certain kinds of beliefs you can’t get the evidence for unless you believe them first. One example is jumping over a chasm or gap on a hiking trail. You can’t successfully jump over the chasm and get the evidence that you’re capable of jumping it unless you believe you can do it first.

God is similar in a very specific sense: evidence of God’s presence in your life is only available to you if you believe first.

Imagine your heart is a room with a door. God could be shining a floodlight at the door all the time, but if you don’t open the door a crack, God’s light will never be able to shine through. I now believe that God can do a lot of amazing things, but God doesn’t impose. It’s up to all of us to crack open our doors.

Once you do, you can start to get experiential evidence. This might be feeling loved, experiencing peace and joy that surpass your previous understanding, or unusual confidence or resilience amidst troubles. It might be a sense of forgiveness beyond what you’ve known before. Or it might be experiences of healing and personal growth—often of issues that you’ve tried to heal multiple ways.

The greatest hypothesis of all was out there waiting to be tested—and I wasn’t participating!

The leap of faith is a leap for truth

I used to think that faith was a betrayal of the truth. If I wanted to be loyal to the truth, I needed to stick to the “bare facts” provided by science. I shouldn’t ever claim anything beyond them, on the off chance the claim might be false.

However...

When it comes to God (as well as many other things, such as what it means to be a good person), the only way to find out what’s true is to put the belief into play. It’s to embrace a hypothesis, act on it, and see what happens.

When I jolted up out of bed that night, I realised that throughout my entire life I had thought that I was being loyal to the truth, but what I was actually doing was standing on the sidelines. The greatest hypothesis of all was out there waiting to be tested—and I wasn’t participating! The human species is in its infancy. There’s so much we don’t know about existence. What if the universe is lovingly Created? What if there are dimensions beyond what we can see and touch?

The truly courageous thing, I now believe, is the opposite of what I’d always thought. It isn’t to refrain from belief. It’s to dare to believe.

The verdict

That night, I decided I would try to get data about God. I’d walk into a life of prayer, worship, and faith. I’d work on re-interpreting my story with God in it. I’d identify biases or misconceptions I had about faith and educate myself about them. I’d ask God to help me see, feel, and believe, if He was there.

I’m less than a year in. But today I’m sleeping better, healing deep emotional wounds, overcoming unhealthy habits, finding peace, stepping deeper into joy, and experiencing feelings of invulnerability where I used to feel the most vulnerable. This sense of invulnerability is beyond anything I’ve ever experienced before, like a spring of confidence and peace welling up from depths beyond me. I consider this data for God.

Might I be wrong? Absolutely. But at the end of the day I am just one person. All I can do is go out and get some data and share what I find, contributing my little piece to the species-wide quest for the truth of things.

So go out and get your data. Take a chance on God, if you like. Crack open your door. See if light shines through. Let me and others know what you find.