In 2022 I had the opportunity to attend the launch of Football and Religion: Tales of Hope, Passion & Play, a mixed media exhibition with works by Ed Merlin Murray, at the Aga Khan Centre Gallery. The exhibition explored the relationship between football and religion and how the two are often connected, with players praying on the pitch and fans observing religious rituals in tandem. The exhibition also examined football’s ability to champion social causes, promote marginalised voices, and create opportunities for inclusion and diversity

The accompanying historical exhibits also revealed important collaborations with a variety of organisations and specialists in the field of football and religion. Among the archive material shown, books such as Thank God for Football! reveal that nearly one third of the clubs that have played in the English FA Premier League owe their existence to a church, while Four Four Jew: Football, fans and faith and Does Your Rabbi Know You Are Here? uncover a hidden history of Jewish involvement in English football.

In an associated essay, ‘Football Is More Than A Secular Religion’, Dr Mark Doidge, Principal Research Fellow in the School of Sport and Health Sciences at the University of Brighton, noted: “Sport and religion are intimately entwined throughout history. Ancient Greek funerary games were seen as the most fitting way of honouring the death of heroes. The Olympics were held in honour of Zeus, which is why the ancient site of Olympia is home to sanctuaries, temples, and sports facilities.”

Sport metamorphosed into a practice of effort, competition, and record-setting, sanctioned by artists in works that reinforced the cult of sporting heroes, relayed by the press.

While not focusing specifically on religion, as did the Aga Khan Centre exhibition, exhibitions organised for the Paris 2024 Olympics are also exploring stories of sport as culture, impacting on gender, class, race, representation, celebrity, science, and art.

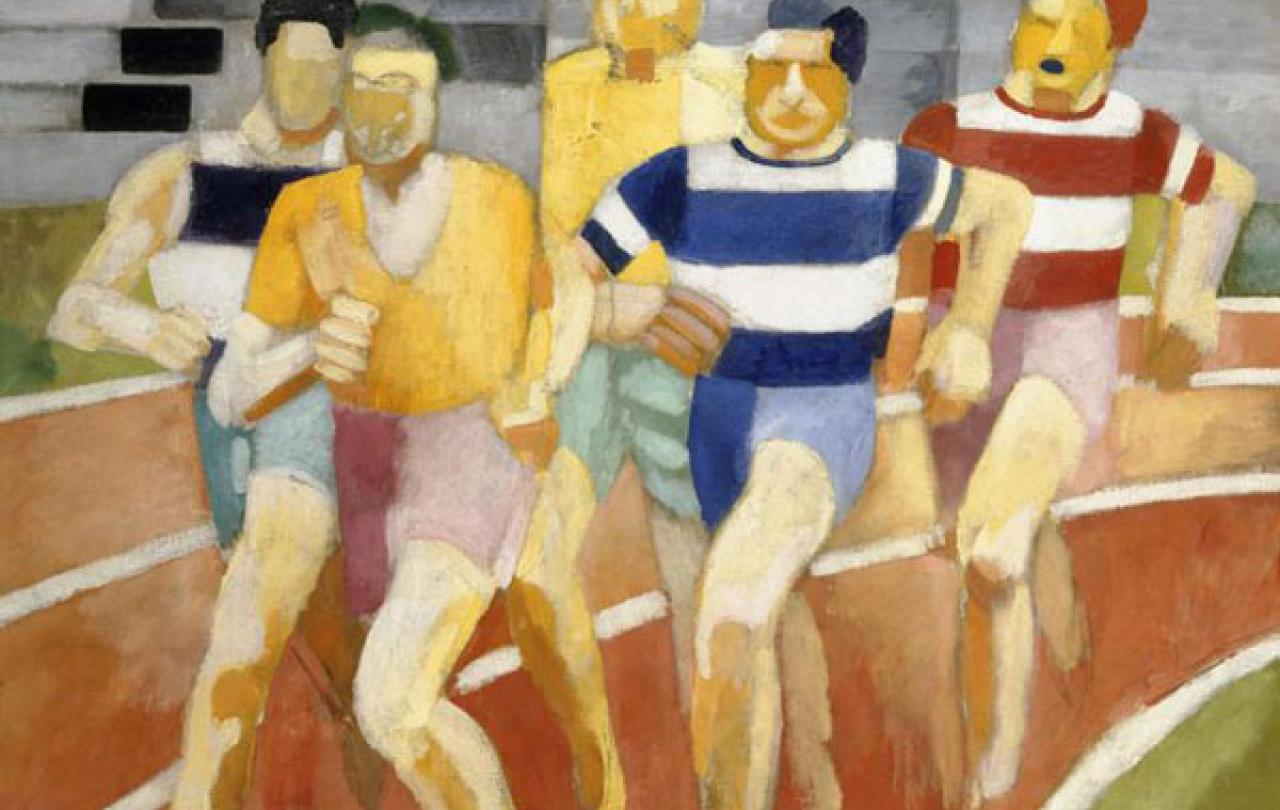

En Jeu! Artists and Sport (1870-1930) at Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, builds up a portrait of the society of the second half of the nineteenth century, which gradually took pleasure in taking advantage of its free time to pursue sporting and leisure activities on land or water. Ranging from Impressionism to Cubism, the exhibition shows how sport and sportspeople were made into icons of modernity and the avant-garde. It also explores the ethical challenges and aesthetic aspects of how sports were perceived by artists such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas and examines the metaphorical meanings of the heroic figure of the artist as a sportsperson, characterized by determination, stamina and a form of resistance.

The changing social codes of sporting circles, where venues became theatres of physical prowess, are also examined. Sport metamorphosed into a practice of effort, competition, and record-setting, sanctioned by artists in works that reinforced the cult of sporting heroes, relayed by the press. Artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Paul Signac identified with the qualities of determination and endurance of these sportspeople who sought to surpass themselves.

Paris 1924: Sport, Art and the Body at Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge explores how the modernist culture of Paris shaped the future of sport and the Olympic Games as we know and love it today. The exhibition looks at a pivotal moment when traditions and trailblazers collided, fusing the Olympics’ classical legacy with the European avant-garde spirit. Paris 1924 was a breakthrough that forever changed attitudes towards sporting achievement and celebrity, as well as body image and identity, nationalism and class, race and gender.

The fusion of modern Parisian cultural style with the Olympics’ classical inheritance gave the event a striking visual impact. Curators Caroline Vout, Professor of Classics, University of Cambridge and Professor Chris Young, Head of the School of Arts and Humanities University of Cambridge say: “The exhibition explores the look and feel of Paris 1924 as trailblazing and traditional, local and global, classical and contemporary. It brings together painting, sculpture, film, fashion, photography, posters and letters.”

The exhibition also highlights the extraordinary achievements of the Cambridge University students who won no fewer than 11 Olympic medals for Great Britain that year, including the sprinter Harold Abrahams whose story inspired the award-winning film Chariots of Fire.

Regular congregation at a sacred space to perform collective rituals creates a ‘collective effervescence’...

Paris 1924-2024: the Olympic Games, a mirror of societies at the Shoah Memorial in Paris highlights the issue of prejudice and discrimination, past and present by drawing on a century of the Olympic Games. Bringing together emblematic images of these sporting events, archive documents, films, extracts from the sporting press and personal accounts, the exhibition reveals the Games to be marked by friendship and excellence, but also as capable of being used for political ends which often reflect deep-seated trends in our societies. The exhibition pays particular attention to the Berlin Olympic Games organised by Nazi Germany in 1936 and to the athletes interned at Drancy during the Second World War. It also shows that the values of Olympism can be a real lever in the fight against racism and anti-Semitism and for a better society.

Taken together, these exhibitions highlight the development of sport as a culture in ways that have a wide impact on society, including religion. In his essay, Mark Doidge highlights the work of the French sociologist Emile Durkheim who ‘identified that the key social components of religion are the foundational components of society’. Doidge notes that “Regular congregation at a sacred space to perform collective rituals creates a ‘collective effervescence’ where the individuals become a community and identify themselves as such”. He also notes the similarities with sport which provides a “way of understanding who we are - who we socialise with, how we see other people, and the ways in which we interact with others” – and which is, like life, “about rivalries and competition, solidarity and teamwork, division, and unity”.

These similarities can lead some to privilege sport over religion but Doidge argues that sport “should recognise that religion is a key part of many people’s identity and sense of self, and work hard to be inclusive for all”.

En Jeu! Artists and Sport (1870-1930), 4 April to September 2024, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

Paris 1924: Sport, Art and the Body, 19 July to 3 November 2024, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Paris 1924-2024: the Olympic Games, mirror of societies, 6 May to 9 June 2024, The Shoah Memorial, Paris.