Watch the parade

Ceremony is beating a retreat. Although wheeled out for major life events: naming newborns, marriage and bidding last goodbyes, and for grand state and civic occasions, standing on ceremony is frowned upon in day-to-day life. Ritual is treated warily, in case it creates an ‘us and them’ chasm between participants, seen as elite, and spectators, presumed to be condemned to disempowering passivity.

But what if, far from alienating people, the power of ritual, ceremony and spectacle could be a force for engagement? The church and military both have a history of creating, reinventing and refreshing rituals to meet changing social needs. The army chaplaincy is an invention of the late eighteeneeth century, responding to the move towards more settled communities of soldiers, requiring spiritual support. Drumhead altars, a centrepiece of November’s Festival of Remembrance, have origins going back into the mists of time, but quite how far back it is hard to say with certainty.

Processions and festivities for holy days are more apparent in Catholic countries, with Seville’s Semana Santa parades springing to mind, but well -dressing, May Queens, harvest festivals and Remembrance Sunday reveal a continued desire for entwining of church and community rituals, across faith traditions.

Art’s ability to step into the ceremonial space and create moments of communion, as well as giving voice to underrepresented groups, has been evident since Surrealism. British Surrealist Eileen Agar’s crustacean strewn ‘Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse’, 1936, attracted collective gasps when she wore it in London. In Sao Paolo in 1931, Brazilian modernist Flavio de Carvalho had to be rescued by police when he walked, hatless, in the opposite direction of a Corpus Christi procession, and the crowd wanted to beat him up.

Artists can also create spectacles of togetherness and joy.

Berwick Barracks is a challenging site for community arts. The massive walls and monumental stone-grey interior of Britian’s first purpose-built barracks is reminiscent of eighteenth century experiments in prison design. Even the windows on the living quarters, confirming it is not a prison, are tiny-paned and meanly spaced, like an afterthought dotted reluctantly on the overbearing grey expanse.

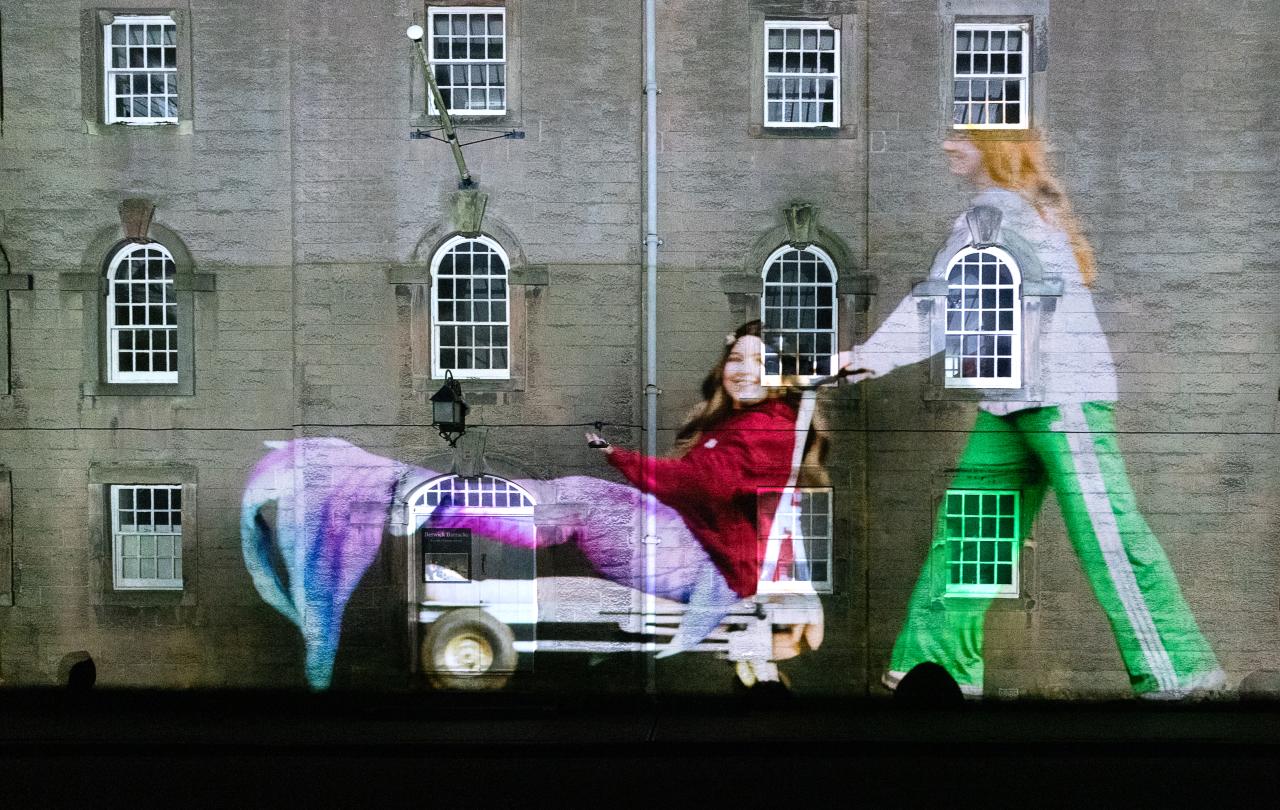

But over the weekend of Berwick Parade, the barracks’ forbidding walls turned into a living portrait of the border town. Under a piercingly brilliant starlit sky – it was the night of the six planet alignment – an audience gathered in the middle of the parade ground to watch themselves, neighbours, friends and family members move across the barrack walls. Artist Matthew Rosier’s projection at x10 magnification transformed the townspeople into giants, and the forbidding military structure of Berwick Barracks into a canvas for joy and creativity.

Berwick Parade shows you can draw community from a stone, forbidding, large grey stones at that. Paraders and audience were dazzled and dignified, seeing themselves anew.

The dancing, riding and processing images were soundscaped by music from the repertoire of the Kings Own Scottish Borderers, who have their ceremonial base, and museum, at the barracks, accompanied by the Melrose and District Pipes and Drums. Positioned by the main gate, the musicians set the expectation of spectacle with the rousing music associated with marching bands, as Scotland the Brave gave way to Mairi’s Wedding, and then a medley of upbeat, om-papa outdoors tunes.

Over 30 minutes, topped by veterans of the Kings Own Scottish Borderers and tailed by hi -vis vest wearing Berwick Parade production staff carrying metal barriers, a parade including processing clergy and the Bishop of Berwick, conga-ing medics in scrubs from Berwick Hospital, brownies, boys’ and girls' football teams, civic leaders in mayoral regalia, Morris, Highland and flamenco dancers, and midlife wild swimmers, shimmied across the walls. Berwick Riders Association were filmed on small ponies, so the magnified projection would not crop the riders into headless torsos. A wheelchair user crossed the expanse of barracks wall wearing a mermaid’s tail. Everybody involved was simultaneously true to life and larger than life.

Consisting of 850 characters, some of Berwick’s residents played more than one role. “Ooh there’s Cheryl again” commented a spectator next to me, as another pageant of figures travelled across barracks’ perimeter.

Speaking to Rossier the following morning, he revealed Parade participants had been filmed in the barracks, travelling across a10 metre stage. Magnification made these sequences large enough to cover one wall of the rectangular parade ground. Editing and projection created the appearance of participants entering at one corner and disappearing around the next.

Movement filmed across short distances opened up participation in the Parade to people with mobility and health issues, in a way that physically journeying around the whole parade ground, repeated over three nights, never could.

Filmed over six bitterly cold days, choreographer Chloe Sayers had to keep participants’ spirits and energy up as they devised ways of travelling across 10 metres that represented their personality, role and creativity. Sayers specialises with creating events with the public rather than professional dancers, and says that enabling people to express themselves through movement in spaces not always thought of as welcoming, breaks down barriers and creates a sense of ownership.

Some of the funniest moments in Berwick Parade were rare breeds sheep hogging the limelight like divas, and children clowning around with policemen’s helmets and clipboards. Rosier says primary school years are a sweet spot for performance. ”I love the energy kids bring. We had all age groups, but the six- to 10-year-olds bring so much energy. They just bounce. They have no inhibitions but are good at following instructions. At 12 or 13 heads start to drop and they become more self-aware.”

Rosier drew on his Irish Catholic mother’s tradition of ceremony and celebration with food and drinking, whether for a wedding or a funeral, to make Berwick Parade a fun place to hang out - food stalls included - beyond the performance. “I want people to have a nice time and not be subservient to the thing they have come to watch.”

Berwick Parade shows you can draw community from a stone, forbidding, large grey stones at that. Paraders and audience were dazzled and dignified, seeing themselves anew.

At King Charles’ coronation, the church’s ceremonial superpower was on display to the world. And as artists demonstrate, ceremony does not have to be confined to great occasions. Churches in all traditions can draw on their legacy of historic touchpoints between faith and community, to reinvent, reinstate and refresh rituals to engage with people’s contemporary concerns and hope.

Community groups taking part in Berwick Parade.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief