I remember recently when I was reduced to a data point. I became an inconvenient name on a spreadsheet.

"Your services are no longer needed. We have to let you go," he stated with feigned empathy. Just like that, years of my work and contributions - hours, days, weeks, months - ceased to matter. I didn't matter. "HR will contact you shortly to explain the final details. Again, I am truly sorry."

The Zoom meeting ended, the camera went blank. I sat in my home office, staring at the blank screen of the company-issued laptop. The only sounds were the disheveled thoughts scrambling in my head and the gentle hum of the fan circulating cool air from the ceiling above. All went quiet. Just like that I was reduced to a KPI - a key performance indicator.

Having spent years in the business world, I'm well-acquainted with its dynamics, including hiring and firing. I recognize ambition and its relentless pursuit of progress. Still, it felt like a personal blow, like a scene on Instagram or YouTube you replay endlessly on loop, trying to comprehend, trying to make sense of it all.

As your value is quantified and found wanting, a sacred inner part of you perishes. In that moment, it’s hard to feel the wonder and mystery of your creation. You don’t feel what for centuries has been called the imago Dei - that we humans are made in God’s image. Instead, you think about how you were just told “we don’t need you.” You think about paying your bills? How will this impact your career? Where will you find your next job?

As a leader, I understand metrics are crucial for business. However, this pervasive culture of metrics has warped our perception of worth. Instead of marveling at the wonder of being made in the image of God, we have become trained to value only what can be counted. We’ve become both deaf and blind to the unquantifiable beauty of human existence.

We’ve prioritized metrics over people. We’ve created a world where efficiency presides over meaning and productivity overshadows purpose. Ironically, this has crippled entire organizations, not optimized them. Critical components like morale, engagement, and productivity are at an all time low. Just check the numbers. (See what I did there)

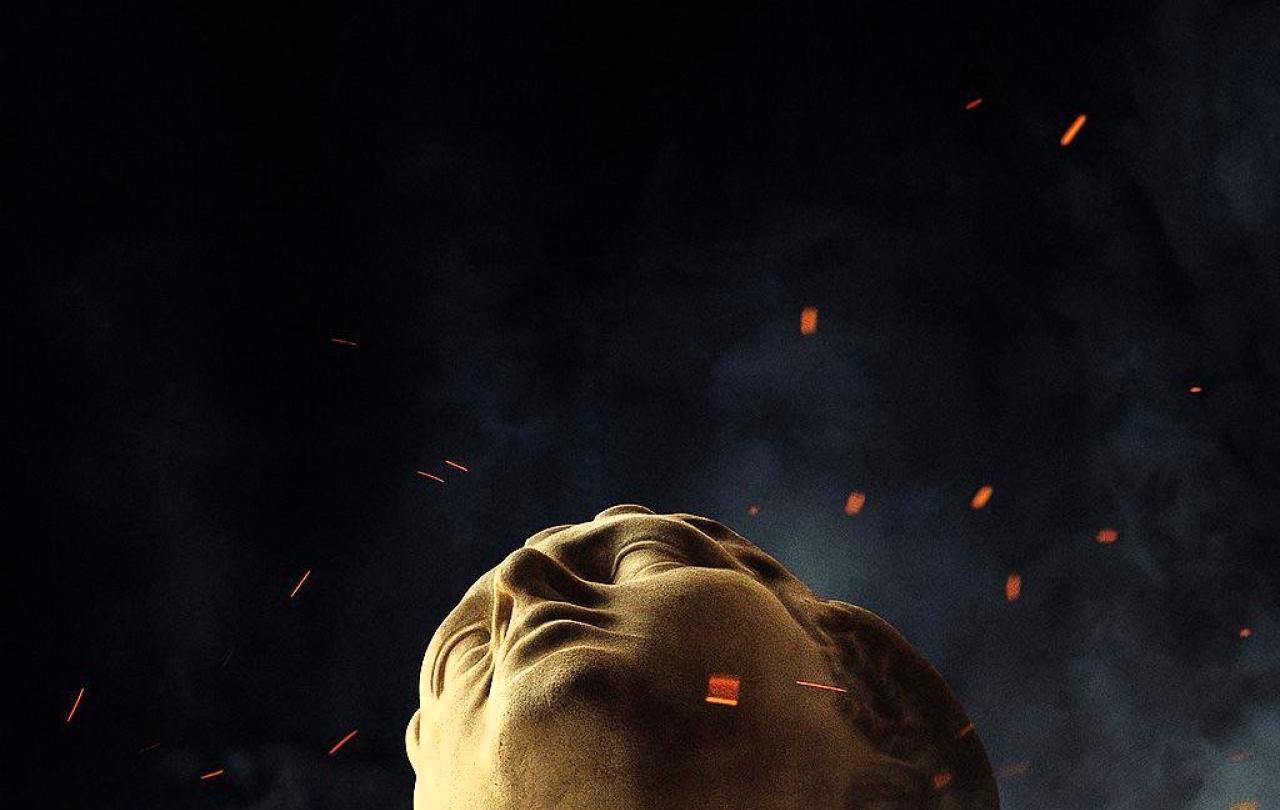

We have built a ruthless culture defined by a dehumanizing machinery of metrics. People have become problems to be optimized rather than mysteries to be revered.

If we let our job define us and if as leaders we let it define our mystery and those we lead, we succumb to a cancerous, spiritual violence. To treat a person as a set of outputs is to willinging deny our capacity to reflect a divine truth.

Does it have to be this way?

William Blake's poem, "The Divine Image," eloquently conveys a core theological principle: humanity mirrors the divine, embodying God's very image. We are an irreducible, immeasurable value.

For Mercy, Pity, Peace and Love

Is God, our father dear

And Mercy, Pity, Peace and Love

Is Man, his child and his care.

Are we imago Dei? Are we the very image of God the first chapter in Genesis speaks of?

Is this true? Are we always irreducible, immeasurable? Or is this just a conversation to have in a broader discussion when contemplating humanity’s place in the cosmos?

What about the workplace? What about when human worth is distilled into key performance indicators that then become the only thing measured, the only things that defines a person’s worth? What happens when our irreducible human value, this imago Dei is distilled to mere data points on business dashboards? To KPIs.

On one hand, nothing happens; we are still a complex mystery of God’s creation. We are still immeasurable, irreducible. We are imago Dei. On the other hand, something does happen to the person. Something sacred is expunged. Our infinite complexity like emotions, dreams, quirks, ideas, feelings, and virtues are reduced and transcribed into metrics and evaluated against random data sets. Perhaps this is where the shallow quip originates? “It’s not personal. It’s just business.”

I mean I get it. In the business world, we are a metrics driven culture, quantifiable data points are seemingly the only identifier of worth. It drives the business, right?

We read in our company handbooks that, “our people make the difference.” In reality, we all know that data is the true currency. It is here, I argue, that the soul gets buried beneath spreadsheets and the image of the divine is lost within a myriad of data sets.

We must raise a quiet but profound rebellion.

Our spirit of God’s very image that thrives in a mutual wonder and shared humanity cannot be replaced by a zero-sum race for higher scores.

Ask someone at work “How are you doing?”, actually listen to them and engage, and only then ask, “How are you doing with your targets?” Metrics are important, but the person behind them is essential.

When we become our job or when we think those we work with are defined only by how well they do their job, we are all vulnerable to this sacred loss. Our goal is not our job. Our purpose is not how and if we hit our metrics. Instead, our sole aim should be to seek how to better understand this mystery of this life - this imago Dei - that we have been given and how to share it with others.

This reminds me of the saying, "Not everything worthwhile can be measured, and not everything that can be measured is worthwhile."

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief