There’s a trend doing the rounds on TikTok which is attracting a fair amount of comment; the practice of taking (at least) a day in bed to recuperate when you’re running low on energy. Gen Z are - with characteristic directness - calling it ‘bed rotting’.

At first, this sounds like nothing new. People have been taking to their bed for centuries. Gen X might’ve called it vegging out, millennials would call it a duvet day.

From the discourse that’s sprung up about bed rotting though, it seems like some bigger questions are being explored around this trend. Firstly, Gen Z are reclaiming the need to stay in bed by branding it as a form of self-care. This picks up on some broader wellbeing trends online, where people are trying to decouple their sense of worth from their productivity. This train of thought picked up steam during the Covid-19 pandemic, and seems to continue to be something people are wrestling with.

As others are pointing out... is getting to the point of needing a day to rot in bed is really a good approach to self-care?

I rather like the visceral nature of the phrase ‘bed rotting’ and I’m sure that, whichever generational cohort we fall into, we can all relate to the occasional need to totally switch off to refresh and recalibrate. However, as others are pointing out, a second consideration is whether getting to the point of needing a day, to rot in bed, is really a good approach to self-care. Or would more preventative measures be the better way to care for yourself? Some commentators on TikTok have suggested that a combination of other gentle activities would actually be better at delivering the desired results than lounging in bed alone.

Dr Saundra Dalton Smith suggests in her book Sacred Rest that there are seven types of rest: physical, mental, spiritual, emotional, sensory, social and creative. Whilst bed rotting provides perhaps three or four of these types of rest, it may not provide the long-term refreshment sought if it doesn’t nurture the other parts of us as well.

Should we all just be expected to mindfulness our way out of a mental health crisis or yoga our way out of chronic pain?

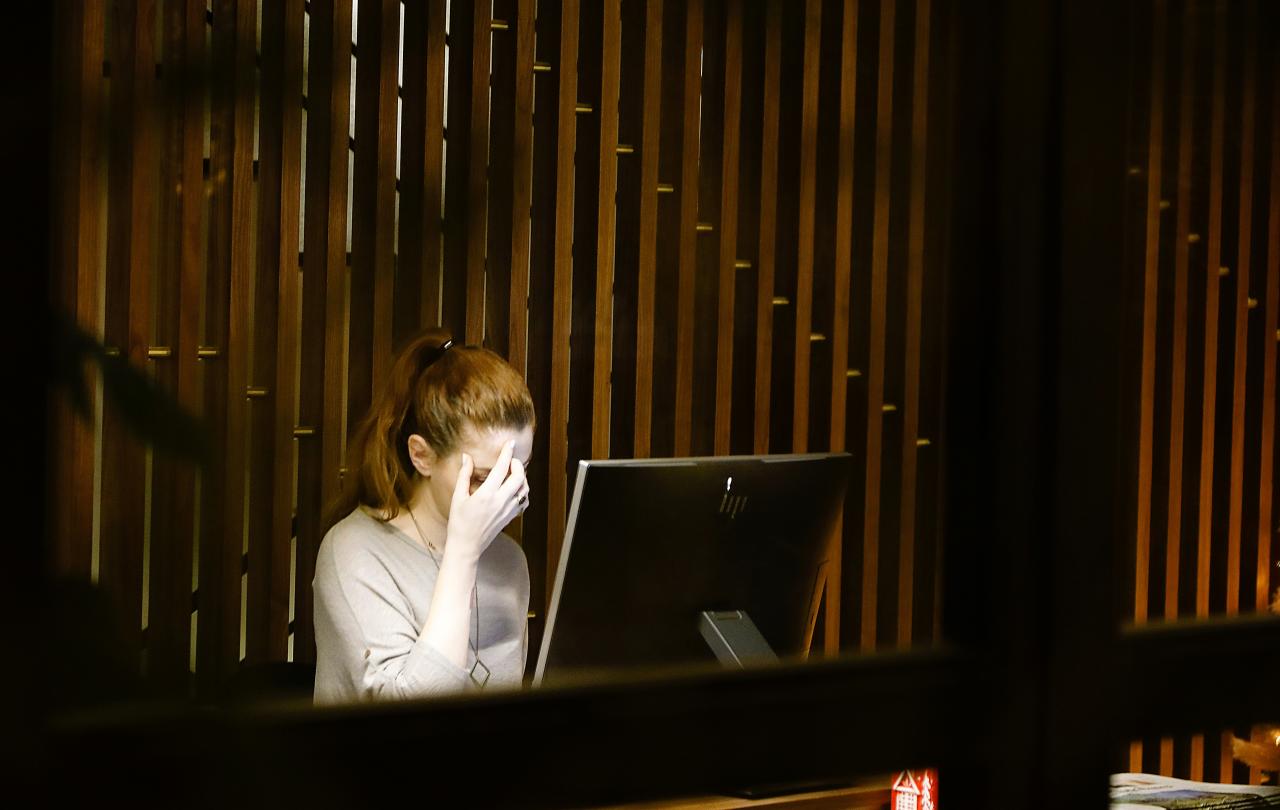

While framing this extreme need for rest as self-care may give people permission to stop and reduce the stigma of doing nothing, it also puts the onus on the individual. I think the risk of self-care narratives in general is precisely in the focus they put on the self. While it can be healthy and empowering to take action to improve your wellbeing, it also draws attention away from the societal systems and structures that are contributing to everyone feeling so exhausted all the time. Should we all just be expected to mindfulness our way out of a mental health crisis or yoga our way out of chronic pain? Or should we be looking more widely at what is going on in the world?

This tension between taking responsibility for my own wellbeing but also reflecting on how I relate to the wider concepts of work, productivity and success is a very live, everyday issue for me. I have fibromyalgia, a chronic health condition characterised by fatigue and widespread muscular pain. Whilst conventional medicine gives some relief, I have to manage my energy levels very closely and intentionally pace myself to avoid my symptoms flaring up, though sometimes it is out of my control.

Unfortunately, if I were to let myself get to the point of desperately needing to bed rot it might take me a week or two to fully recover. I have to resist the urge to say yes to every invite and make sure I have a balance of work, rest and play in each week. This is helped by the privilege of being able to schedule my work around my own needs, it would certainly be much harder if I was tied to a very strict working pattern. In a way, it's like I have an early warning system for burnout, and I’ve become very attuned to fluctuations in my mood, energy or pain levels that might indicate the equilibrium is off.

As part of my energy management strategies, I have also found that the ancient practice of sabbath from the Judeo-Christian tradition has helped me to both take regular time to rest and to remind myself that I am a human being, not a human doing.

In Genesis, the opening poem of the Hebrew scriptures, we hear that after six days of hard work creating the universe, God rested on the seventh day. For thousands of years, Jews and Christians have attempted to learn from this and incorporate a day of rest into each week. The practice also exists in Islam.

Each Sunday I try to do as little as possible and particularly to disconnect from digital channels, because I know they often take more energy than they give me.

The way that this plays out in people’s lives ranges from very strict observance to more loosely held rules and rituals. However, you approach it, there is much to be learned from this ageless wisdom. I initially began practicing sabbath myself when I went freelance and realised how easily I could end up working seven days a week if I didn’t pay attention. This was six months or so before the first Covid-19 lockdown in the UK and I was extremely grateful to have established this habit in my life when that occurred.

For me, sabbath isn’t just ensuring I’m squeezing rest into each week but also creating rhythm. It punctuates my week and gives everything else breathing space. Each Sunday I try to do as little as possible and particularly to disconnect from digital channels, because I know they often take more energy than they give me.

In The Ruthless Elimination of Hurry, John Mark Comer helpfully suggests two simple criteria to decide whether something is permissible on the sabbath. Is it rest or worship? If it’s not one of those two things then it can wait. For me, worship usually means going to church, but for you that could be something else that helps you connect to something bigger than yourself and experience a sense of wonder. Perhaps immersing yourself in nature, or engaging with an awe-inspiring work of art.

Another helpful piece of advice about sabbath I heard from Annie F. Downs on Instagram:

“If you work with your hands, sabbath with your mind. If you work with your mind, sabbath with your hands.”

As someone who spends most of my working week creating content on a computer, this is a useful reminder not just to read and journal on my sabbath but to swim, crochet or cook as well.

Lastly, Jesus said “The sabbath was made for man, and not man for the sabbath”. This reminds me to do sabbath in a way that is life-giving for me, even if that looks different to what works for others. These guidelines have helped me establish a practice of sabbath which provides clarity and routine, whilst being expansive enough to allow me to give myself whichever type of rest I need at a given time. Occasionally I do just bed rot, but usually I do things that restore me and bring me joy, whether that’s taking a walk or cycle if I have the energy or simply taking my lunch to the beach.

Of course, I’m not always perfect in the way I sabbath. That’s why it’s called a practice. But I do notice I flag later in the week if I’ve skip it. So, even if I occasionally switch the day or bend one of my rules for a practical reason, I keep coming back to it.

If you don’t already, I really encourage you to try the routine of sabbath for yourself. Pick a day of the week that works for you, put some boundaries in place, try it for a few weeks and adjust accordingly. Treat it as an experiment, a gift to yourself and perhaps as a little way to opt out of the madness of modern life for a beat. And by all means, bed rot if you need to. As Brené Brown says:

“It takes courage to say yes to rest and play in a culture where exhaustion is seen as a status symbol.”