What makes a genius different? I used to think a genius was someone who excelled at everything. With an IQ of around 150, whatever a genius does will be brilliant.

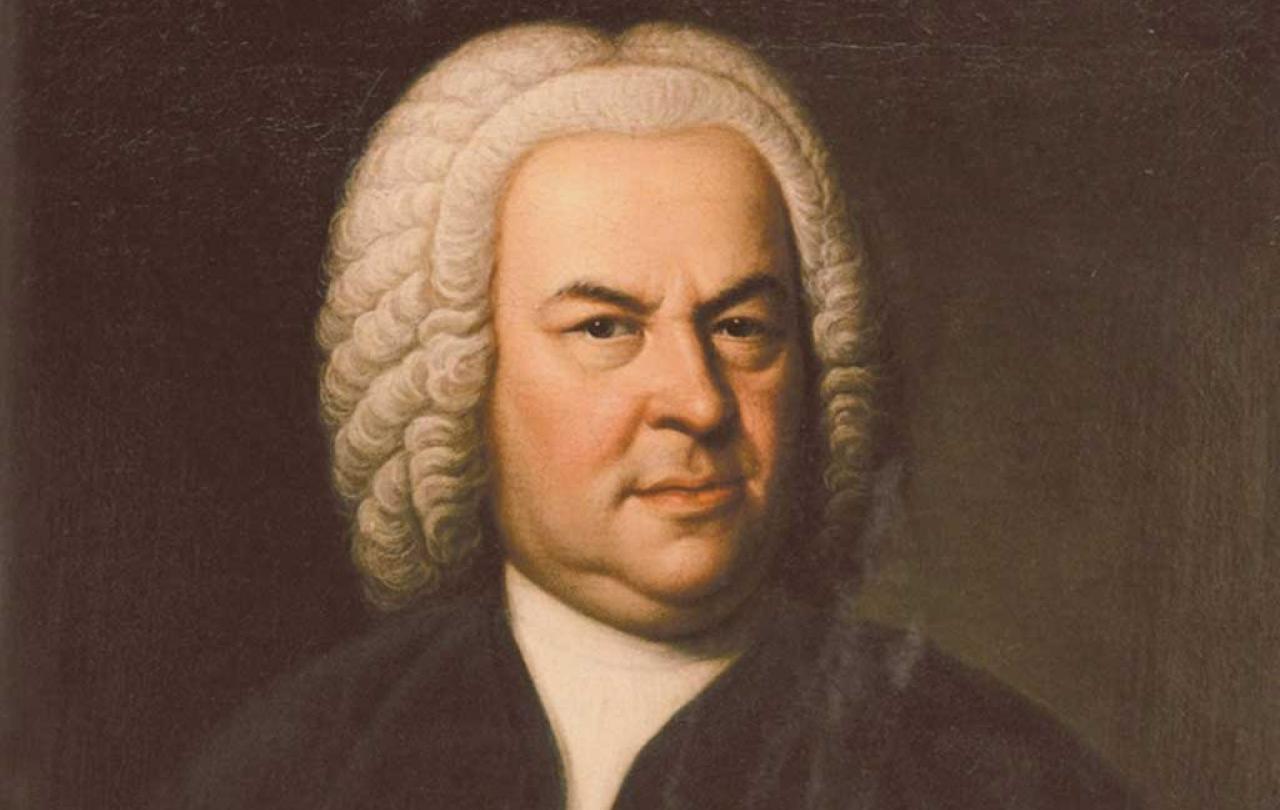

In fact, most of the people we call geniuses excel at just one main thing, and it’s how they excel at it that makes them different. The German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) is a good example.

In all sorts of ways, Bach was unexceptional. He didn’t lead an especially dramatic life. He was a working musician, with a stint as a court musician, and much longer stints as a church music director, latterly in Leipzig. In this respect, there were many like him at the time.

He travelled very little. Socially, he was fairly conventional and conformist for his day, certainly not the sort to rock any political boats. He produced a huge quantity of music, certainly, but then so did many of his contemporaries. He was a Lutheran Christian. That is, he belonged to a wing of Christianity that followed the teachings of Martin Luther, the reformer who ignited the Protestant Reformation. And as a Luthern he was devout, but not exceptionally so for this time. He knew his Bible well, but so did hundreds of others in his day.

He wasn’t a great writer of words. Like many musicians, he could be grumpy. He didn’t suffer fools gladly and was a hard taskmaster: he hated it when people tried to get out of doing hard work. He was not particularly well known during his lifetime, certainly not an international celebrity.

In short, if we had met him socially, I doubt if we would have found it a memorable experience.

And yet he changed the face of Western music, not simply “classical” music but every musical style from concert to folk, jazz to bebop, early pop (Lennon and McCartney were huge fans) to hard rock. Nothing was the same after Bach. Over the last 300 years, there is hardly a single musician who has not been impacted by him in one way or another, even if they might not know it.

So in what does Bach excel? Why is he the most revered musician in history? People answer this in different ways, but for me, it comes down to something very simple: he turns the Christian life into sound to a degree no one before or after has come close to matching. This is not to say he is always preaching at you. He does proclaim, certainly, but the musical sounds he generates do not generally send “messages”. Rather, they help you feel what it’s like to live in this world—and understand the world—as a Christian.

Take for example his mammoth masterpiece that tells the story of the suffering and death of Jesus as told by Matthew in the New Testament: the St Matthew Passion.

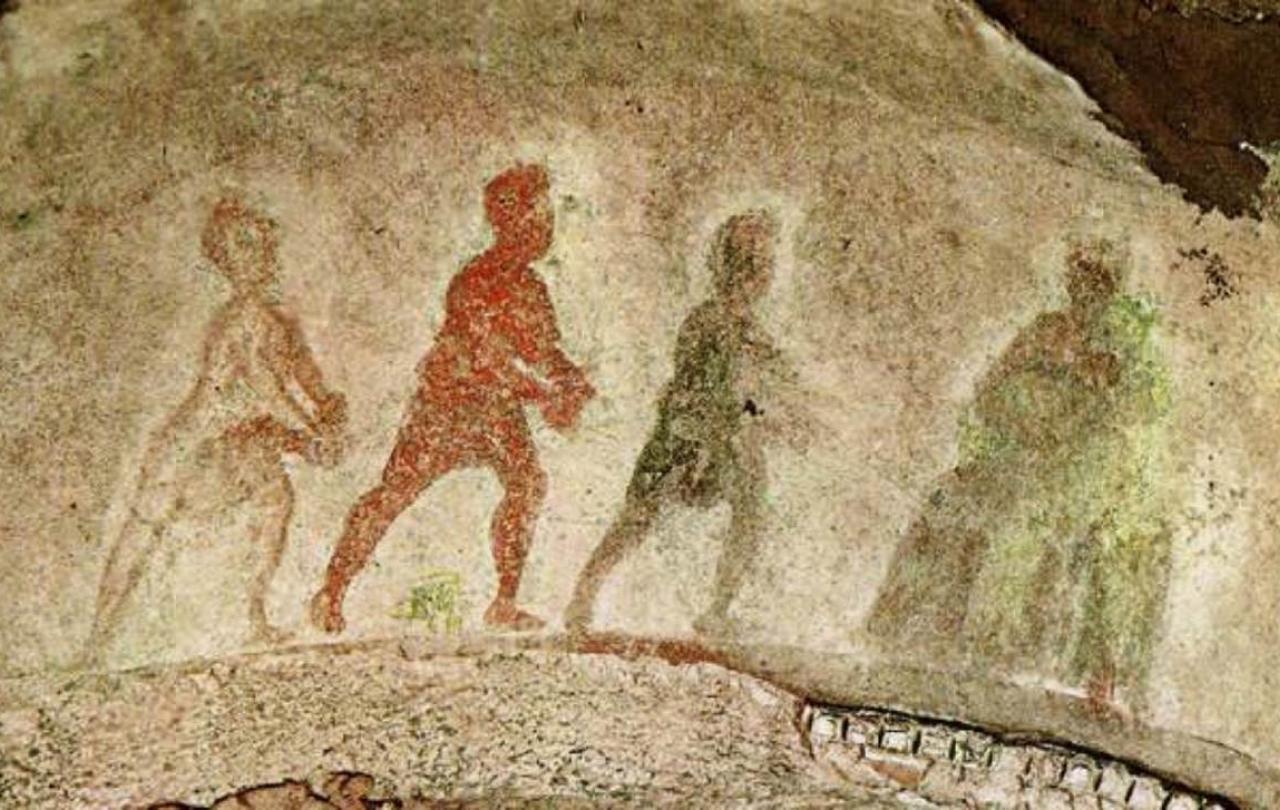

Right from the start, you do not simply hear about or observe the drama; you are taken inside it. In the opening scene Jesus trudges on the via dolorosa to his crucifixion. String basses and cellos pound away on one note in a faltering, dragging rhythm; other instruments tug away from each other in fierce dissonance. All this is in a dark minor key. We are made to feel in our bodies the slow, lumbering, doom-laden march of this man to his execution. But that is not all. On top of this, two choirs enter, singing to each other: the one asks puzzled questions (who is this?) and the other replies by unfolding the meaning of this strange procession: the condemned man is carrying the weight of the world’s human guilt. But that is not all. Over this, a third choir enters (usually a boy choir in today’s performances). These are the singers of the heavenly Jerusalem, far above the action, intoning an ancient hymn (“Lamb of God...”). Fittingly, they sing in a secure rhythm, and in a positive (major) key. Here God is winning back, healing his broken world, our world. Bach piles all these layers on top of each other so we hear them all at once—something only music can pull off (it is impossible with words alone). We trudge with Jesus as he identifies with us at our worst, yet at the same time we are surrounded by an eternal assurance that here God is doing his climactic work.

Listen to St Matthew Passion

Another especially pointed example of Bach’s “inside” view comes when Bach tackles one the most famous scenes in Matthew’s story. Peter, supposedly Jesus’ most loyal follower, has just publicly denied he ever knew him. And this despite pledges of unswerving loyalty. He retches inside as his beloved leader is led away to his trial and death. A tenor soloist sings Matthew’s simple sentence: “And Peter went out and wept bitterly.” That is about as terse as you can get. But Bach strings these words out over a tortured, tormented melody—close to the sound of a person wailing with grief. When we reach the word “out” (as in “Peter went out”), Bach has the tenor sing a top B, the highest note he sings in the entire work. A musical “going out” is linked to a physical and metaphorical “going out”. And all this happens over the most anguished, dissonant, harsh harmony. It’s painful to listen to—which is, of course, the point. Again, Bach is not depicting something at a distance. He doesn’t even want us to feel sorry for Peter, for this is not about someone else. It’s about us. He wants us to us to feel something on the inside: that we have betrayed the One who more than anyone else has been prepared to die for us.

Listen to Peter's story

Two glimpses of a Christian mind in action. But just as remarkable is what Bach can do without any words at all. He gave birth to hundreds of instrumental pieces, and he seems to have believed these were just as important as his vocal works. That’s because he believed musical notes—melodies, chords, motifs, riffs, harmonies—carried their own power to help us sense what it feels like to live in a world brought into being by the Christian God.

From the most unpromising motifs, the most unremarkable clusters of notes, he can weave music of astounding richness.

A lot of Bach’s music for instruments comes alive when heard in this light. It is as if we are being invited to listen to a cosmos in sound. A towering example is his famous Chaconne from the Partita in D minor for solo violin. Most scholars recognise that more than any other musician before or since, Bach knows how to get the most out of the least. From utterly unpromising motifs, unremarkable clusters of notes, he can weave sounds of astounding richness. In this piece he weaves fifteen minutes of music from a simple four-bar chord pattern, a seemingly endless series of variations of every mood and colour. The impression is of an infinity of possibilities, a boundless abundance. Even when he does eventually draw things to a close, as many scholars have noted, we are left with the impression this could have gone on ad infinitum.

Listen to Chaconne, played by Itzhak Perlman

Very much the same applies to the even longer Goldberg Variations for keyboard, whose breathtaking overflow is evoked well in words from the distinguished Bach scholar, John Butt:

“There is something utterly radical in the way that Bach’s uncompromising exploration of musical possibility opens up potentials that seem to multiply as soon as the music begins. By the joining up of the links in a seemingly closed universe of musical mechanism, a sense of infinity seems unwittingly to be evoked.”

Bach is, in effect, giving us a musical imagination of something basic to Christian faith: that we live in a world in which the Creator God is constantly at work, drawing a potentially infinite number of options out of even the most unpromising material: which of course, we should take to include ourselves—ordinary, frail, and stumbling human beings.

Not only that, Bach invites us to hear the interweaving of radical consistency and radical openness. Listen to a minute or two of the Chaconne and press pause at almost any point; it’s very hard to predict what will happen next, even if you know the style well. And yet what does happen makes perfect sense. In other words, it sounds as if it’s being improvised. This is why jazz musicians are so intrigued by Bach’s music. There is nothing deterministic about it: we are not inside a machine, or something that must unfold in the way it does. And yet it is anything but arbitrary or absurd-sounding. Bach seems to have sensed what many contemporary physicists will confirm: we don’t live a fixed universe in which the future is simply the unwinding of the past, and yet the world has a regularity to it, a dependability—it makes sense. In Bach’s imagination—as in the Bible itself—God is not arbitrary or fickle. God is the improvisor, we might say: faithful and surprising at the same time.

Finally, we mention one other striking feature of Bach’s sound world that is hard to miss: the way it can encompass extreme joy and extreme pain. Bach was no stranger to grief and death. Both his parents died before he was ten years old. He fathered twenty children, but seven of those died immediately after birth or in infancy. He was out of town when his first wife, Maria Barbara, died; he was never able to say his farewells.

To hear Bach at his most dissonant, taking us to the very edge of coherence, listen to Variation 25 from the Goldberg Variations (used in Ingmar Bergman’s 1963 film “The Silence”).

Listen to Variation 25

We do not know if he was thinking of the crucifixion of Jesus here (he openly tackled this theme elsewhere in music of extraordinary sorrow) but in this piece he plumbs such dark depths it is hard to believe there is no connection at all. For Lutherans, the death of Jesus was the very centre of God’s engagement with the world, the point where God identified most intensely with us in our darkest depths.

And yet, even in pieces of this kind, as Bach scholars have often noted, and as we hinted above, Bach will often “overreach”, spill out of the parameters he sets for himself. The ecstasy you will hear in the "Et Resurrexit " of the Mass in B Minor is a good example: where the raising of the crucified Jesus from the dead is translated into music that might well be called hyper-energetic. Again, Bach doesn’t allow us to observe and contemplate things from a safe distance. He is trying to catch us up into a life that by its very nature is uncontainable. As with so much of Bach's music, dance is the fundamental dynamic here: it is hard to keep still when surrounded by the cascading momentum. With a twinkle in his eye, he adds an orchestral postlude that by the conventions of his time was wholly unnecessary, gratuitous, excessive—a fitting testimony to the superabundant character of what he believed happened on Easter Day. In the midst of a society surrounded by the brute physical reality of death, including the deaths of members of his own family, Bach carries us into an overspill of energy that pulls against the downward, contracting “running down” of the physical world, evoking a “running up”—in his imagination, the life of the resurrection body to come.

Listen to the Et Resurrexit