There is something both inspiring and unnerving about Elon Musk. He is a game-changing pioneer and innovator in so many industries pivotal to our future: rockets, electric cars, solar panels, batteries, satellite Wi-Fi, and Artificial Intelligence. But he is also no stranger to scandal, controversy and allegation. In his latest biography, author Walter Isaacson explores the toxicity as well as the ingenuity that has come to be associated with the richest man on the planet. As he reveals Musk’s series of successes, and what has been sacrificed to acquire them, I found myself going on an emotional journey: from compassion to awe to outrage.

Compassion: a man familiar with misery

In the opening chapter of his book Isaacson draws attention to the trauma in Elon’s childhood. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Elon was socially awkward at school. When he once pushed back at a boy who bumped into him, he was being beaten up so badly his face was unrecognisable. When he returned from hospital Musk reports how his father reacted: “I had to stand for hours. He yelled at me and called me an idiot and told me that I was just worthless.” There are a number of similar stories from Musk’s seemingly brutal childhood. Errol Musk, Elon’s father, features heavily in a series of shocking revelations including that he slept with his own stepdaughter, fathering two children with her. The background of Musk’s chaotic childhood, his experience of domestic abuse, and his series of fractured relationships provides a context for some of the strange, indeed outrageous things catalogued in the book.

Having worked for many years with children in the care system and with refugee experience, I understand a little about the impact of trauma and how it can change the brain in profound ways. There is a great deal of evidence showing how adverse childhood experiences can cause long-lasting impact on decision-making, impulse control, relationship building, mental health management and emotional regulation. While many turn to alcohol, drugs or self-harm as coping mechanisms, others, perhaps like Musk, channel the pain into ambitions and achievements.

I found myself feeling profoundly sorry for Musk. No child should have to experience such prolonged cruelty both at school and at home. All of us need to know that we are loved and valued, independent of anything we have done or anything that has been done to us.

Awe: a man of magnificent moments

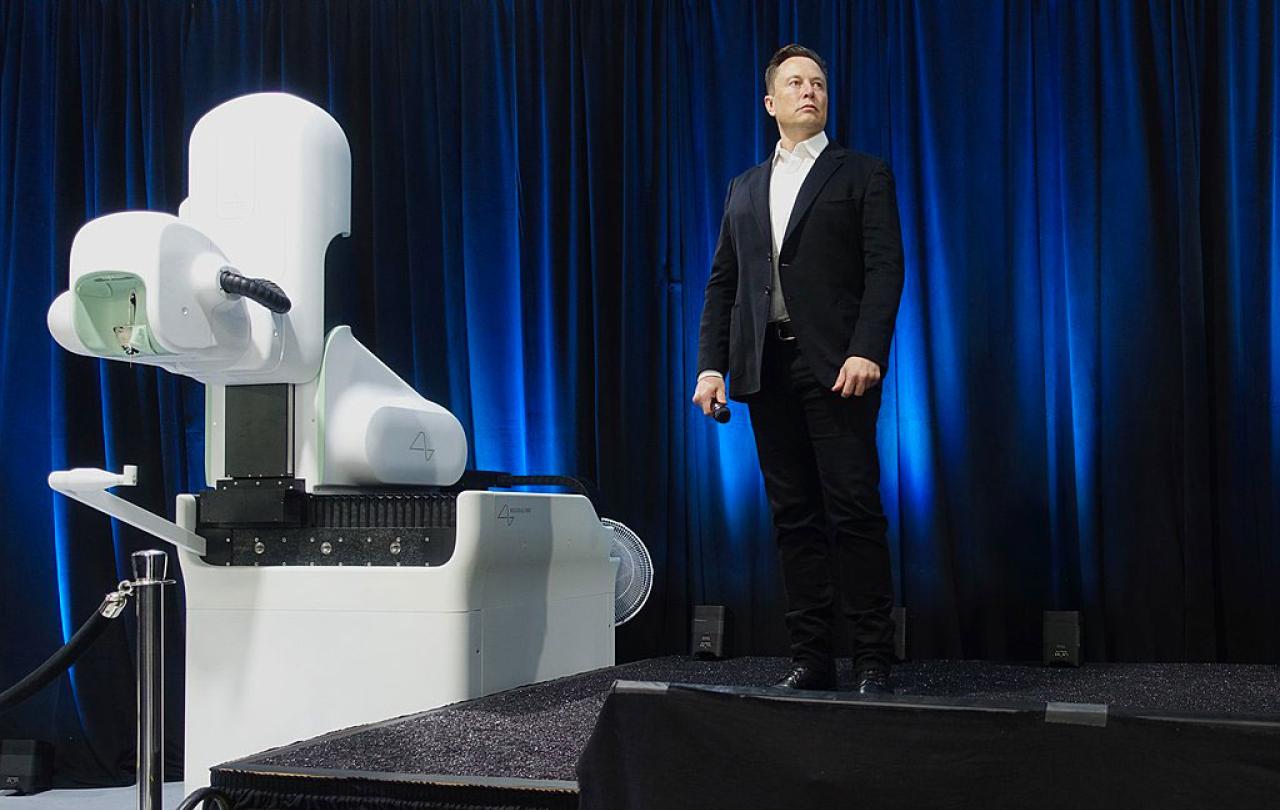

Musk’s ideas have revolutionised so many industries. The automotive industries move to electric power owes a lot to the innovation of Tesla. His Space X programme is currently changing the way we think about space travel. His company was the first to create self-landing reusable rockets and was the first private owned company to develop a liquid-propellant rocket that reached orbit; the first to launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft; the first to send a spacecraft to the International Space Station; and the first to send astronauts to the International Space Station. He is also trying to revolutionise Artificial Intelligence (AI) through his company xAI - a direct competitor to Open AI even though he was one of their early backers.

Musk has a complex relationship with AI as he is not only one of the lead innovators in the field but also the most prominent of the 33,000 signatories of a letter calling for a pause to ‘Giant AI Experiments’ until there is, in Musk’s words, “a regulatory body established for overseeing AI to make sure that it does not present a danger to the public."

AI, alongside each of the other major interest areas in Musk’s work, is way beyond any dreams I ever had of a futuristic world. Musk has managed not only to imagine the unimaginable, but to find a way to get there with impressive speed, scale and sustainability values. The more I read about the innovations involved in each step of each project, the more impressed I am with the genius behind them.

Outrage: a man without a moral compass?

Despite Walter Isaacson’s clear respect for all Musk is achieving, he paints a warts-and-all picture of his book’s subject. We see a man who is ruthless in his hirings and firings, who has often treated staff and colleagues badly. In 2018, he famously called a rescue diver, helping to save teenage boys from a flooded cave in Thailand, a ‘paedo’, in what seemed to be a reaction to a snub to his offer of using his minisub.

In light of these sorts of outbursts, and his apparent desire to save the world from looming environmental disaster, it is no wonder that some people have accused Musk of having a messiah complex. Yet if he does, it is a very different mindset from the true messiah. He appears to me to be morally, emotionally and financially the polar opposite to the Jesus whose willingness to sacrifice himself on behalf of those in need was central to his claim to be sent from God. From the way Isaacson describes Musk, I see him more as a man on a mission to save himself than to save those around him.

The future? Musk, a man at a crossroads.

Isaacson closes his book with the following analysis:

“But would a restrained Musk accomplish as much as Musk unbound? Is being unfiltered and untethered integral to who he is? Could you get the rockets to orbit or the transition to electric vehicles without accepting all aspects of him, hinged and unhinged? Sometimes great innovators are risk-seeking man-children who resist potty training. They are reckless, cringeworthy, sometimes even toxic. They can also be crazy. Crazy enough to think they can change the world.”

I find this a disconcerting epilogue to the book. It suggests that we can pardon toxicity in the name of innovation, that the ends always justify the means, that morality and decency can take second place to advancement and wealth. If this stance were to be applied to, say, the development of AI, Musk’s fears of it becoming a danger to the public may sadly well be realised.

While factors such as grand ambition, the contribution to society, early years trauma, and mental health struggles may provide a robust explanation of why a person may be toxic, toxicity itself can never be excused. No amount of wealth can undo the harm toxic masculinity does to those around us. No amount of charitable giving can buy a person a generous spirit or moral compass. No amount of environmental awards can create the sort of world we really want to live in in the future – a world where people treat one another with the respect they need and deserve.

Elon Musk’s biography is unusual because he is still mid-journey. Who knows what else he may go on to achieve or fail at, to create or destroy? Will his AI revolution be a force for good, helping to create a better future for those who need it most, or will it become the behemoth of the doomsayers? What will future editions add to his biography? Is being ‘untethered’ really integral to who Musk is, or can he change? The visionary in me would love to imagine a redemption and transformation story for Musk that can unleash a compassionate generosity that could even overshadow his creative genius. The sceptic in me fears he may end up doing more harm than good.