Scottish Parliament’s Assisted Dying bill will go to a stage one vote on Tuesday 13th May, with some amendments having been made in response to public and political consultation. This includes the age of eligibility, originally proposed as 16 years. In the new draft of the bill, those requesting assistance to die must be at least 18.

MSPs have been given a free vote on this bill, which means they can follow their consciences. Clearly, amongst those who support it, there is a hope that raising the age threshold will calm the troubled consciences of some who are threatening to oppose. When asked if this age amendment was a response to weakening support, The Times reports that one “seasoned parliamentarian” (unnamed) agreed, and commented:

“The age thing was always there to be traded, a tactical retreat.”

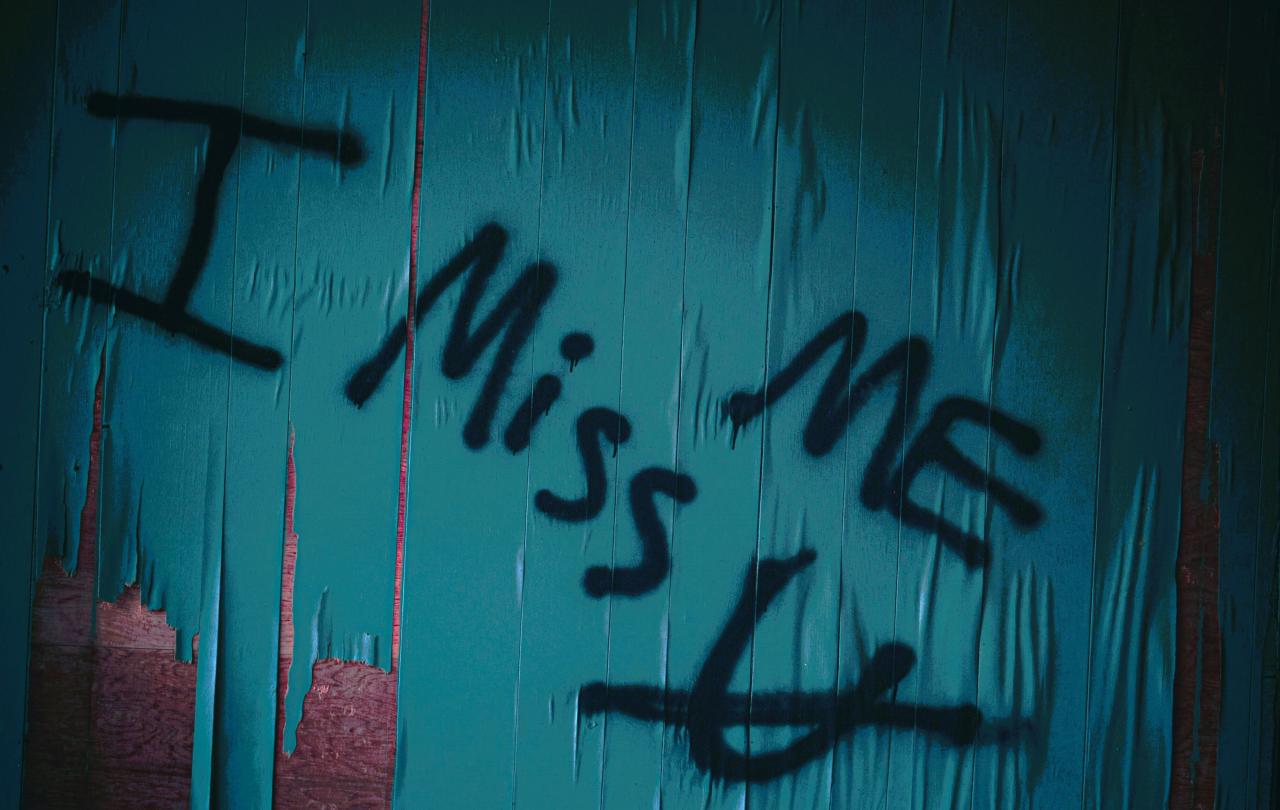

The callousness of this language chills me. Whilst it is well known that politics is more of an art than a science, there are moments when our parliamentarians literally hold matters of life and death in their hands. How can someone speak of such matters as if they are bargaining chips or military manoeuvres? But my discomfort aside, there is a certain truth in what this unnamed strategist says.

When Liam McArthur MSP was first proposed the bill, he already suggested that the age limit would be a point of debate, accepting that there were “persuasive” arguments for raising it to 18. Fortunately, McArthur’s language choices were more appropriate to the subject matter. “The rationale for opting for 16 was because of that being the age of capacity for making medical decisions,” he said, but at the same time he acknowledged that in other countries where similar assisted dying laws are already in operation, the age limit is typically 18.

McArthur correctly observes that at 16 years old young people are considered legally competent to consent to medical procedures without needing the permission of a parent or guardian. But surely there is a difference, at a fundamental level, between consenting to a medical procedure that is designed to improve or extend one’s life and consenting to a medical procedure that will end it?

Viewed philosophically, it would seem to me that Assisted Dying is actually not a medical procedure at all, but a social one. This claim is best illustrated by considering one of the key arguments given for protecting 16- and 17- year-olds from being allowed to make this decision, which is the risk of coercion. The adolescent brain is highly social; therefore, some argue, a young person might be particularly sensitive to the burden that their terminal illness is placing on loved ones. Or worse, socially motivated young people may be particularly vulnerable to pressure from exhausted care givers, applied subtly and behind closed doors.

Whilst 16- and 17- year-olds are considered to have legal capacity, guidance for medical staff already indicates that under 18s should be strongly advised to seek parent or guardian advice before consenting to any decision that would have major consequences. Nothing gets more major than consenting to die, but sadly, some observe, we cannot be sure that a parent or guardian’s advice in that moment will be always in the young person’s best interests. All of this discussion implies that we know we are not asking young people to make just a medical decision that impacts their own body, but a social one that impacts multiple people in their wider networks.

For me, this further raises the question of why 18 is even considered to be a suitable age threshold. If anything, the more ‘adult’ one gets, the more one realises one’s place in the world is part of a complex web of relationships with friends and family, in which one is not the centre. Typically, the more we grow up, the more we respect our parents, because we begin to learn that other people’s care of us has come at a cost to themselves. This is bound to affect how we feel about needing other people’s care in the case of disabling and degenerative illness. Could it even be argued that the risk of feeling socially pressured to end one’s life early actually increases with age? Indeed, there is as much concern about this bill leaving the elderly vulnerable to coercion as there is for young people, not to mention disabled adults. As MSP Pam Duncan-Glancey (a wheelchair-user) observes, “Many people with disabilities feel that they don’t get the right to live, never mind the right to die.”

There is just a fundamental flawed logic to equating Assisted Dying with a medical procedure; one is about the mode of one’s existence in this world, but the other is about the very fact of it. The more we grow, the more we learn that we exist in communities – communities in which sometimes we are the care giver and sometimes we are the cared for. The legalisation of Assisted Dying will impact our communities in ways which cannot be undone, but none of that is accounted for if Assisted Dying is construed as nothing more than a medical choice.

As our parliamentarians prepare to vote, I pray that they really will listen to their consciences. This is one of those moments when our elected leaders literally hold matters of life and death in their hands. Now is not the time for ‘tactical’ moves that might simply sweep the cared-for off of the table, like so many discarded bargaining chips. As MSPs consider making this very fundamental change to the way our communities in Scotland are constituted, they are not debating over the mode of the cared-for’s existence, they are debating their very right to it.