Recent worries expressed by Anthropic CEO, Dario Amodei, over the welfare of his chatbot bounced around my brain as I dropped my girls off for their first days at a new primary school last month. Maybe I felt an unconscious parallel. Maybe setting my daughters adrift in the swirling energy of a schoolyard containing ten times as many pupils as their previous one gave me a twinge of sympathy for a mogul launching his billion-dollar creation into the id-infused wilds of the internet. But perhaps it was more the feeling of disjuncture, the intuition that whatever information this bot would glean from trawling the web,it was fundamentally different from what my daughters would receive from that school, an education.

We often struggle to remember what it is to be educated, mistaking what can be assessed in a written or oral exam for knowledge. However, as Hannah Arendt observed over a half century ago, education is not primarily about accumulating a grab bag of information and skills, but rather about being nurtured into a love for the world, to have one’s desire to learn about, appreciate, and care for that world cultivated by people whom one respects and admires. As I was reminded, watching the hundreds of pupils and parents waiting for the morning bell, that sort of education only happens in places, be it at school or in the home, where children themselves feel loved and valued.

Our attachments are inextricably linked to learning. That’s why most of us can rattle off a list of our favourite teachers and describe moments when a subject took life as we suddenly saw it through their eyes. It’s why we can call to mind the gratitude we felt when a tutor coached us through a maths problem, lab project, or piano piece which we thought we would never master. Rather than being the pouring of facts into the empty bucket of our minds, our educations are each a unique story of connection, care, failure, and growth.

I cannot add 8+5 without recalling my first-grade teacher, the impossibly ancient Mrs Coleman, gazing benevolently over her half-moon glasses, correcting me that it was 13, not 12. When I stride across the stage of my village pantomime this December, I know memories of a pint-sized me hamming it up in my third-grade teacher’s self-penned play will flit in and out of mind. I cannot write an essay without the voice of Professor Coburn, my exacting university metaphysics instructor, asking me if I am really saying what is truthful, or am resorting to fuzzy language to paper over my lack of understanding. I have been shaped by my teachers. I find myself repaying the debts accrued to them in the way I care for students now. To learn and to learn to care are inseparable.

But what if they weren’t? AI seems to open the vista where intelligences can simply appear, trained not by humans, but by recursive algorithms, churning through billions of calculations on rows of servers located in isolated data centres. Yes, those calculations are mostly still done on human produced data, though the insatiable need for more has eaten through most everything freely available on the web and in whatever pirated databases of books and media these companies have been able to locate, but learning from human products is not the same as learning from human beings. The situation seems wholly original, wholly unimaginable.

Except it was imagined in a book written over two hundred years ago which, as Guillermo del Toro’s recent attempt to capture that vision reminds us, remains incredibly relevant today. Filmmakers, and from trailers I suspect Del Toro is no different here, tend to treat the story of Frankenstein as one of glamorous transgression: Dr Frankenstein as Faust, heroically testing the limits of human knowledge and human decency. But Mary Shelley’s protagonist is an altogether more pathetic character, one who creates in an extended bout of obsessive experimentation and then spends the rest of the book running from any obligation to care for the creature he has made.

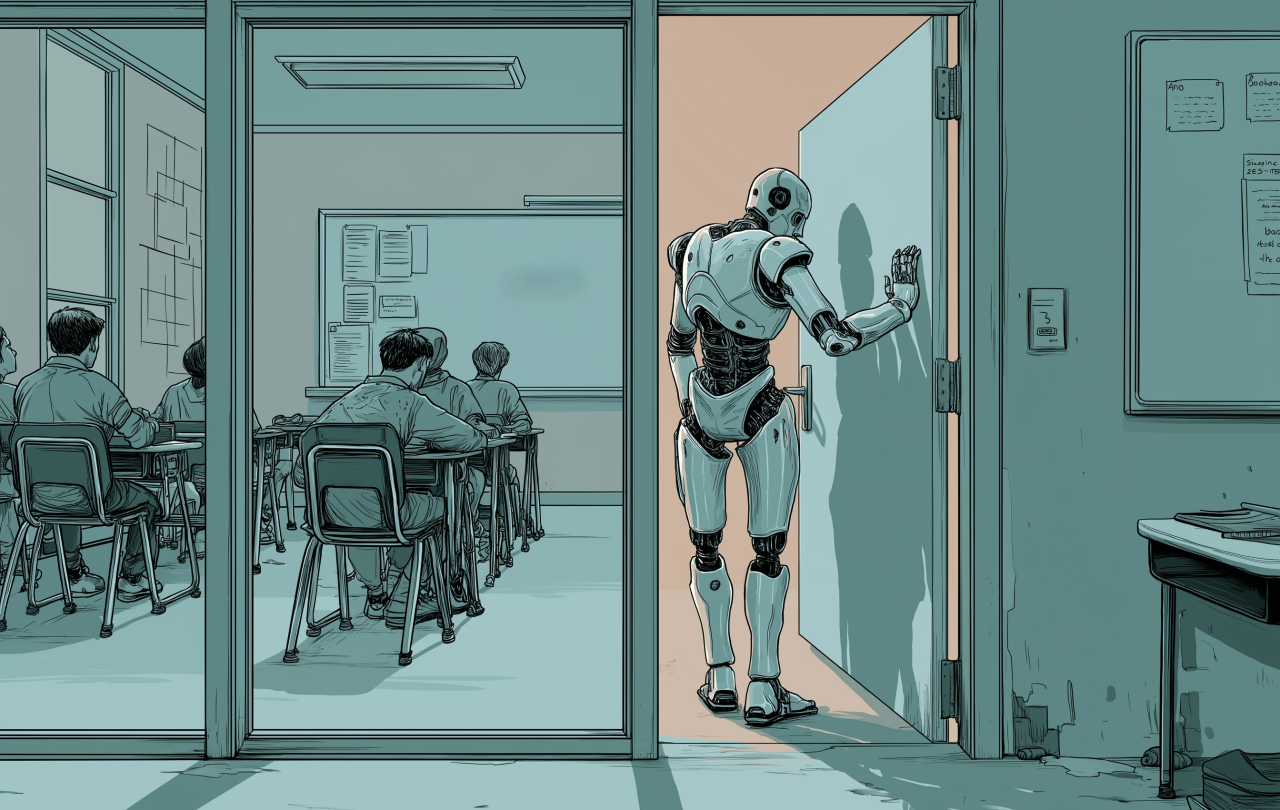

It is the creature who is the true hero of the novel and he is a tragic one precisely because his intelligence, skills, and abilities are acquired outside the realm of human connection. When happenstance allows him to furtively observe lessons given within a loving, but impoverished family, he imagines himself into that circle of growing love and knowledge. It is when he is disabused of this notion, when the family discovers him and is disgusted, when he learns that he is doomed to know, but not be known, that he turns into a monster bent on revenge. As the Milton-quoting monster reminds Frankenstein, even Adam, though born fully grown, was nurtured by his maker. Since even this was denied creature, what choice does he have but to take the role of Satan and tear down the world that birthed him?

Are our modern maestros of AI Dr Frankensteins? Not yet. For all the talk of sentient-like responses by LLMs, avoiding talking about distressing topics for example, the best explanation of such behaviour is that they simply are mimicking their training sets which are full of humans expressing discomfort about those same topics. However, if these companies are really as serious about developing a fully sentient AGI, about achieving the so-called singularity, as much of the buzz around them suggests, then the chief difference between them and Frankenstein is one of ability rather than ambition. If eventually they are able to realise their goals and intelligences emerge, full of information, but unnurtured and unloved, how will they behave? Is there any reason to think that they will be more Adam than Satan when we are their creators?

At the end of Shelley’s novel, an unreconstructed Frankenstein tells his tale to a polar explorer in a ship just coming free from the pack ice. The explorer is facing the choice of plunging onward in the pursuit of knowledge, glory, and, possibly, death, or heeding the call of human connections, his sister’s love, his crew’s desire to see their families. Frankenstein urges him on, appeals to all his ambitions, hoping to drown out the call of home. He fails. The ship turns homeward. Knowledge shorn of attachment, ambition that ignores obligation, these, Shelley tells us, are not worth pursuing. Will we listen to her warning?

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief