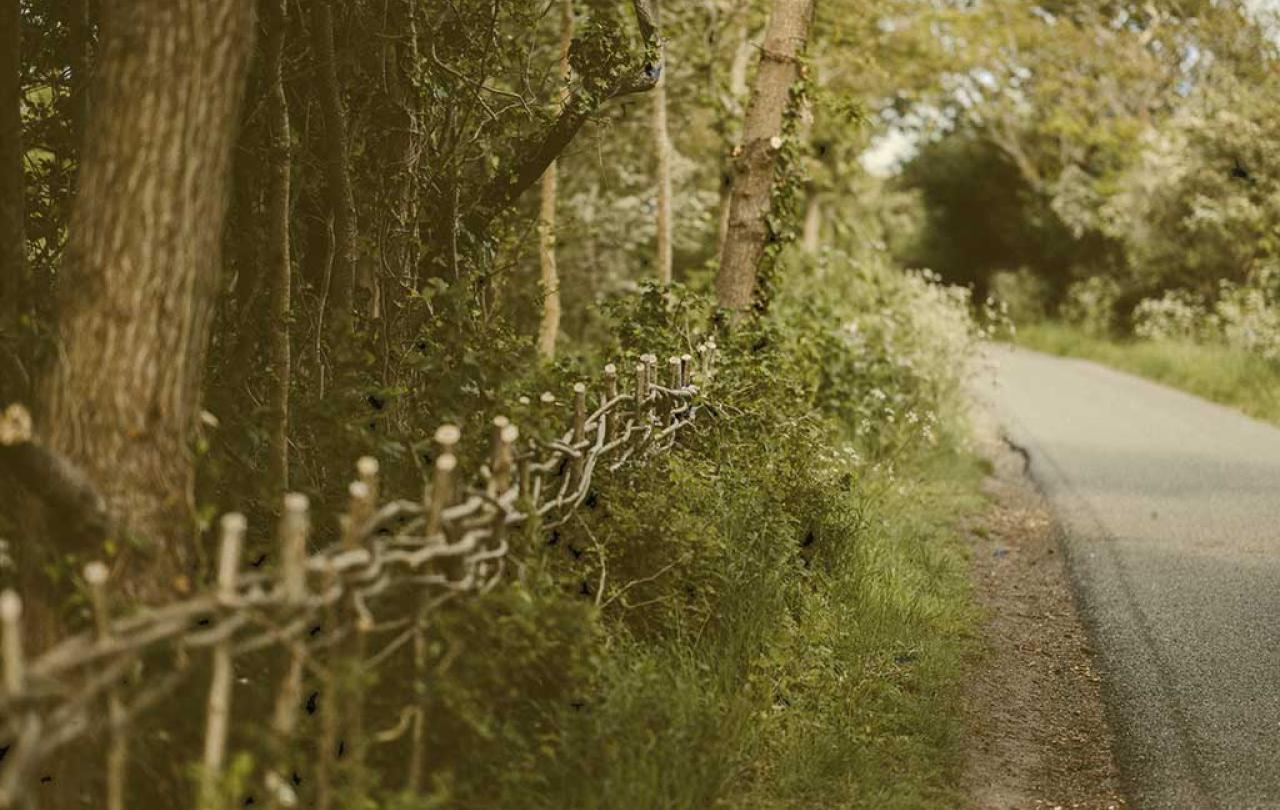

It’s May as I write this, and I’m noticing Iris flowers everywhere. They don’t flower for long, but they are glorious when they do. There is another kind of Iris too - our newborn daughter Iris, born in May under a full moon; appropriately named the ‘flower moon’ in some cultures. And it really was a time of flowers - in her name, and in the Devon hedgerows outside which were bursting into life and nurturing a rainbow of wildflowers - pink campion, creamy hawthorn, yellow celandine, bluebell, violet, endless green. These hedgerows are ancient. ‘Hooper’s formula’ can give an estimate of just how ancient - counting the number of woody shrubs and trees in a 30m section and multiplying by 100 gives a rough estimate (one species for every 100 years). This makes the hedges and sunken earth-banked lanes around us well over 1000 years old, thousands of years in places. They feel essential to the structure of this place.

The layers of land in this part of Devon are overlain and interwoven, sometimes reinforcing what was there before, sometimes obliterating it. Today the threat of obliteration looms larger than ever - development, forestry and rapidly changing agricultural practices all squeeze rural communities and landscapes to the edge. But these old hedgerows and earth banks seem to resist the march of development and ‘progress’ – continuing a line of resistance that stretches back to the local Celtic people resisting Anglo-Saxons, who in turn resisted the Normans. The hedges represent old ways, they hold their ground and ask us to slow down and prioritise other things than convenience and blind progress.

Because for local farmers, it is not convenient to farm these small wonky fields with their thick-hedged edges. In other parts of the country, fields got bigger and bigger as hedges were ripped out, especially during the Second World War when food production was a priority. And the size of fields kept pace with the growing machinery used to farm them. Farmed fields in some parts of the country are now vast. But not here. Outside the window huge tractors thunder past, but they look out of place in these narrow lanes and small fields - old spaces that are less and less able to resist the damage of modern machines.

I think inconvenience is good for love and for neighbourliness. Loving and knowing our neighbours are beautiful intentions, but they can quickly become easy words and abstract concepts.

But whilst these ancient hedgerows are inconvenient for modern farming, they are convenient for life, because things can exist here that wouldn’t if the hedges were removed - biodiversity, soil structure, shelter and food for countless species through the year; species that are under threat from intensive agriculture elsewhere. It is the inconvenience of the hedges and fields here that leaves room for life.

I think about how this is true of other things; how inconvenience might bring life, how it might even be essential for our relationship with things that matter. Two specific things come to mind.

First, I think inconvenience is good for love and for neighbourliness. Loving and knowing our neighbours are beautiful intentions, but they can quickly become easy words and abstract concepts. Putting the idea of neighbourliness into practice will be inconvenient - it will have an impact on me and my life, it will take time and might be awkward at first - but it is where the love and I think the hope is. The future has lately been sounding bleak - heatwaves and wildfires and temperatures higher than climate modelling has predicted; economies in turmoil; never ending conflicts. Loving our neighbour isn’t about niceness, or just for when it’s convenient – it’s for right now as the world burns, it’s for helping us know the world through the lives of others, it’s for rebuilding affection and life on earth.

Second, I have found that inconvenience is good for knowing the Bible. When I first began reading it — curiously but non-committaly as a young adult — the thing that kept me coming back was its beauty. Much of its meaning was lost to me, but its sound and rhythm wasn’t. The Bible is inefficient, inconvenient. It is often impenetrable, mysterious, poetic. And poetry is often inconvenient - it asks us to slow down, to pay attention, to engage imagination and heart and feeling, to re-read something that might not at first be clear. And when its meaning or imagery sticks then it remains, I do not forget it. If the Bible’s authors wanted readers to understand something, to believe something, there are shorter and clearer ways to do so which might even guarantee particular outcomes like belief. But the Bible turns towards poetry and beauty and depth - not transfer of information, not efficiency, not convenience. It asks the reader to slow down and listen, to reach beyond the immediacy of information to another way of being and knowing.

Another Iris speaks - not flower, not daughter, but a singer through our kitchen speakers - Iris Dement is singing a song called Working on a World I May Never See. It makes me think about the importance of investing in hedgerows and neighbours, a declaration of belief that their possibility offers more than the efficiency and productivity they sacrifice. Because we are not made for efficiency, or blind progress, or productivity. I think we are made to love, and to work on a world we may never see; an ask that I increasingly see requires not just ‘development’ and technology and financial investment, but investment in love and neighbours and place. But as the world hurtles on, love seems diminished, its power underestimated or increasingly it seems, unknown. I notice talk of love sometimes met with cynicism, as if it’s a warm fuzzy idea but not something to take seriously, as if it might be world-shaking. But I think it is — or it could be if we let it.

And so I welcome inconvenience, I welcome the courage and patience it teaches me.

The hedgerows and my neighbours and parts of the Bible remind me to take love seriously. They slow me down with their long-way-roundedness, their use of 100 words or species where one would be more efficient, their conjuring of feeling and images where information might be quicker. They ask me to pay attention, they offer beauty, they bring my gaze to things they matter.

In Eric Fromm’s 1956 book The Art of Loving he examines various kinds of love, and then explores the disintegration of love in the modern western world, which is in part he says because:

“Modern man has transformed himself into a commodity; he experiences his life energy as an investment with which he should make the highest profit, considering his position and the situation on the personality market. He is alienated from himself, from his fellow men and from nature. His main aim is profitable exchange of his skills, knowledge, and of himself, his "personality package" with others who are equally intent on a fair and profitable exchange. Life has no goal except the one to move, no principle except the one of fair exchange, no satisfaction except the one to consume.”

(All this written before the arrival of the ‘personality market’ of social media, and before Amazon’s all-consuming invitation to consume).

In examining this commodification of life, and in a line that touches on our fondness for convenience, Fromm says:

“Modern man thinks he loses something—time—when he does not do things quickly. Yet he does not know what to do with the time he gains—except kill it.”

He goes on to argue that love is not a sentiment but a practice; one that involves discipline, concentration, and patience. These aren’t things that a fast-paced attention-deficient society leaves much room for. He says too that

“Love is not primarily a relationship to a specific person; it is an attitude, an orientation of character which determines the relatedness of a person to the world as a whole…”

The hedgerows outside and the poetry of Bible teach me patience and concentration, and they shift my centre of relatedness outwards, from my own need for convenience, from focus on my life and just the people in it, to the wider world - worlds seen and unseen.

Fromm says

“To be loved, and to love, need courage, the courage to judge certain values as of ultimate concern—and to take the jump and to stake everything on these values.”

And so I welcome inconvenience, I welcome the courage and patience it teaches me. The life-giving ‘inconvenience’ of the ever-changing hedgerows, and neighbourliness, and the Bible, and many other things help me to slow down and pay attention, they help me to know and to love, they help me to work on a world I may never see.