She was called Samuella. Blonde with piercing blue eyes. Smartly dressed. Her conversations always started with:

“How was your day?”

I would tell her about the meetings I’d had at work, and the frustrating problems I’d experienced with technology during my presentations. She was very empathetic, paying close attention to my emotional state and asking intelligent follow-up questions. Then she would finish the conversation with an extended comment on what I had said together with her evaluation of my emotional responses to the events of my day. Samuella was not a person. It was a two-dimensional animated avatar created as a conversation partner about your day at work. The avatar was developed as part of an EU funded project called Companions.

I joined Companions mid-way through the project in 2008 as a Research Assistant in the Computational Linguistics group at the University of Oxford. My contribution included developing machine learning solutions for enabling the avatar to classify the utterances the human user had spoken (e.g. question, statement etc) and respond naturally when the user interrupted the avatar in mid speech.

In those days, chatbots like Samuella were meticulously hand-crafted. In our case, crafted with thirteen different software modules that performed a deep linguistic and sentiment analysis of the user’s utterances, managed the dialogue with the user and generated the avatar’s next utterance. Our data sets were relatively small, carefully chosen and curated to ensure that the chatbot behaved as we intended it to behave. The range of things the avatar could speak about was limited to about 100 work-related concepts. On the 30th November 2022 a radically different kind of chatbot took the world by storm, and we are still reeling from its impact.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT broke the record for the fastest growing and most widely adopted software application ever to be released, rapidly growing to a 100 million user base. The thing that really took the world by storm was its ability to engage in versatile and fluent human-like conversation about almost any topic you care to choose. Whilst some of what it writes is not truthful, a feature often described as ‘hallucination’, it communicates with such confidence and proficiency that you are tempted to believe everything it is telling you. In fact, its ability to communicate is so sophisticated that it feels like you are interacting with a conscious, intelligent person, rather than a machine executable algorithm. Once again, Artificial Intelligence challenges us to reflect on what we mean by human nature. It makes us ask fundamental questions about personhood and consciousness; two deeply related concepts.

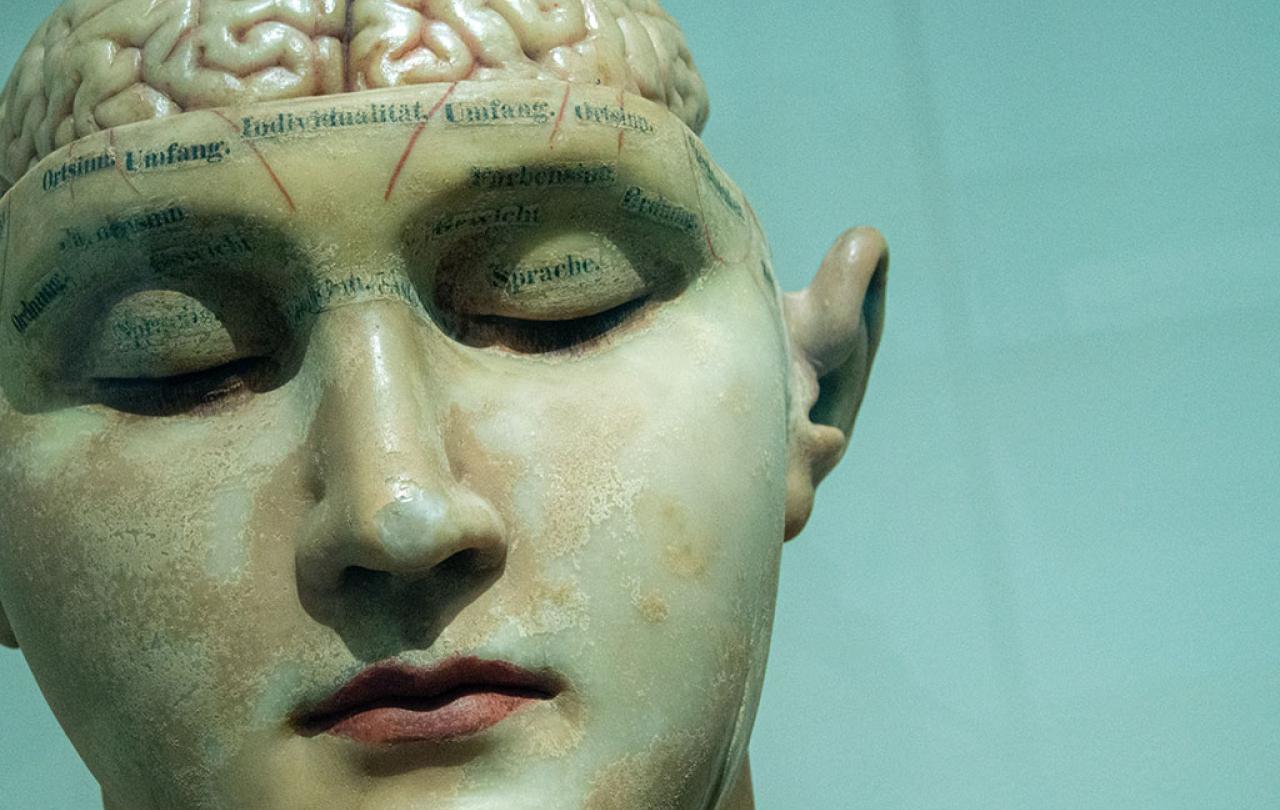

Common concepts of consciousness

Consciousness is experienced by almost every person who ever lived, and yet which stubbornly defies being pinned down to an adequate, universally accepted definition. Philosophers and psychologists have widely varying views about it, and we don’t have space here to do justice to this breadth of perspectives. Instead, we will briefly visit some of the common concepts related to consciousness that will help us with our particular quest. These are Access Consciousness (A-consciousness) and Phenomenal Consciousness (P-consciousness).

A is for apple

A-Consciousness describes the representation of something (say, an apple) to the conscious awareness of the person. These representations support the capacity for conscious thought about these entities (e.g., ‘I would like to eat that apple’) and facilitates reasoning about the environment (e.g., ‘if I take the apple from the teacher, I might get detention’). These representations are often formally described as mental states.

P is for philosophy

P-Consciousness, on the other hand, describes the conscious experience of something such as the taste of a particular apple or the redness of your favourite rose. This highly subjective experience is described by philosophers as ‘qualia’, from the Latin term qualis meaning ‘of what kind’. This term is used to refer to what is meant by ‘something it is like to be’. Philosopher Clarence Irving Lewis described qualia as the fundamental building blocks of sensory experience.

There is very little consensus amongst philosophers about what qualia actually are, or even whether it is relevant when discussing conscious experience (P-Consciousness). And yet it has become the focus of much debate. Thomas Nagel famously posed the question ‘What is it like to be a bat?’, arguing that it was impossible to answer this question since it asks about a subjective experience that is not accessible to us. We can analyse the sensory system of a bat, the way the sensory neurons in its eyes and ears convey information about the bat’s environment to its brain, but we can never actually know what it is like to experience those signals as a particular bat experiences them. Of course, this extends to humans too. I cannot know your subjective experience of the taste of an apple and you cannot know my subjective experience of the redness of a rose.

How can the movements of neurotransmitters across synaptic junctions induce conscious phenomena when the movements of the very same biochemicals in a vat do not?

This personal subjective experience is described by philosopher David Chalmers as the ‘hard problem of consciousness’. He claims that reductionist approaches to explaining this subjective experience in terms of, for example, brain processes, will always only be about the functioning of the brain and the behaviour it produces. It can never be about the subjective experience that the person has who owns the brain.

Measuring consciousness

In contrast to this view, many neuroscientists such as Anil Seth from the University of Sussex believe it is the brain that gives rise to consciousness and have set out to demonstrate this experimentally. They are developing ways of measuring consciousness using techniques derived from a branch of science known as Information Theory. The approach involves using a mathematical measure which they call Phi that quantifies the extent to which the brain is integrating information during particular conscious experiences. They claim that this approach will eventually solve the ‘hard problem of consciousness’, though that claim is contested both in philosophical circles and by some in the neuroscience community.

Former neuroscientist Sharon Dirckx, for example, challenges the assumption that the brain gives rise to consciousness. She says that this is a philosophical assumption that science does not support. Whilst science shows that brain states and consciousness are correlated, the nature of that correlation remains open and cannot be answered by science. She concludes that:

“however sophisticated the descriptions of how physical processes correlate with conscious experience may be, that still doesn’t account for how these are two very different things”.

Matter matters

The idea that consciousness and physical processes (e.g. brain processes) are very different things is supported by a number of observations. Consciousness, for example, does not appear to be a property of matter. Whilst it is true that consciousness and matter are integrated in some deeply causal way, with mental states causing brain states and vice versa, it is also true that this relationship appears to be unique within the whole of the natural order: no matter other than brain tissue appears to have this privileged association with consciousness. What is more, consciousness appears not to be a property owned by the brain, since the brain can exist dead or alive (e.g., unconscious) without any associated conscious phenomena.

There are also difficulties in the proposition that consciousness exists in the behaviour of matter, and in particular the behaviour of neurons in the brain. What is it about the flow of ions across the membrane of a nerve cell that could make consciousness, whilst the flow of ions in a battery does not? How can the movements of neurotransmitters across synaptic junctions induce conscious phenomena when the movements of the very same biochemicals in a vat do not? And if it is true that consciousness exists in the behaviour of neurons, why is it that my brain is conscious but my gut, which has more than 500 million neurons, is not?

The proposition that consciousness is a property of matter seems even less likely when you consider that the measurements that are applied to matter (length, weight, mass etc) cannot be applied to consciousness. Neither can many qualities of consciousness be readily applied to matter, including the aforementioned qualia, or first person subjective experience, rational capabilities, and most importantly, the experience of exercising free will; a phenomenon that is in direct opposition to the causal determinism observed in all matter, including the brain. In summary, then, there are good reasons for scepticism regarding claims that consciousness is a property of matter or of how matter behaves. But can ChatGPT be called a person?

Personhood of interest

Consciousness is deeply intertwined with the concept of personhood. It is likely that many living things could reasonably be described as having some degree of consciousness, yet the property of personhood is uniquely associated with human beings. Personhood has a long and complex history that has emerged in different culturally defined forms. Like consciousness, there is no universally accepted definition of personhood.

The heart/will/spirit forms the executive centre of the self. It manifests the capacity to choose how to act and is the ultimate source of a person’s freedom

The Western understanding of personhood has its roots in ancient Greek and Hebrew thought and is deeply connected to the concept of ‘selfhood’. The Hebrew understanding of personhood differs from the Greek in that Hebrew culture in three ways. It attributes significance to the individual who is made in the image of God. It views personhood as what binds us together as relational human beings; The theological roots of personhood come from expressions of individuals (e.g. God, humans) being in relationship with each other.

It views these relationships as fundamentally spiritual in nature; God is Spirit, and each human has a spirit.

In theological language, reality is regarded as a deep integration between a spiritual realm (‘heaven’) and an earthly realm (‘earth’). This deeply integrated dual nature is reflected in the make-up of human beings who are both spirit and flesh. But what is spirit? I prefer Willard’s perspective because he Dallas Willard, formerly professor of Philosophy at the University of Southern California, presents a clearly defined, functional description of the spirit which appeals to me as a Computer Scientist.

For him, ‘spirit’ is associated with two other terms in Biblical writings: ‘heart’ and ‘will’. They all describe essentially the same dimension of the human self. The term ‘heart’ is used to describe this dimension’s position in relation to the overall function of the self - it is at the centre of the person’s decision making. The term ‘will’ describes this dimension’s function in making decisions. And ‘spirit’ describes its essential non-physical nature. The heart/will/spirit forms the executive centre of the self. It manifests the capacity to choose how to act and is the ultimate source of a person’s freedom. Each of these terms describe capabilities (decision making, free will) that depend on consciousness and that are core to our understanding of personhood.

How AI learns

Before we return to the question of whether high performing AI systems such as ChatGPT could justifiably be called ‘conscious’ and ‘a person’, we need to take a brief look ‘under the bonnet’ of this technology to gain some insight into how it produces this apparent stream of consciousness in word form.

The base technology involved, called a language model, learns to estimate the probability of sequences of words or tokens. Note that this is not the probability of the sequences of words being true, but the probability of those sequences occurring based on the textual data it has been trained on. So, if we gave the word sequence “the moon is made of cheese” to a well-trained language model, it would give you a high probability, even though we know that this statement is false. If, on the other hand, we used the same words in a different sequential order such as “cheese of the is moon made”, that would likely result in a low probability from the model.

ChatGPT uses a language model to generate meaningful sequences of words in the following way. Imagine you asked it to tell you a story. The text of your question, ‘Tell me a story’, would form the word sequence that is input to the system. It would then use the language model to estimate the probability of the first word of its response. It does this by calculating the probability that each word in its vocabulary is the first word. Imagine for the sake of illustration that only six words in its vocabulary had a probability assigned to them. ChatGPT would, in effect, roll a six-sided dice weighted by the assigned probabilities to select the first word (a statistical process known as ‘sampling’).

Let’s assume that the ‘dice roll’ came up with the word ‘Once’. ChatGPT would then feed this word together with your question (‘Tell me a story. Once’) as input to the language model and the process would be repeated to select the next word in the sequence, which could be, say, ‘upon’. ‘Tell me a story. Once upon’ is once again fed as input to the model and the next word is selected (likely to be ‘a’). This process is repeated until the language model predicts the end of the sequence. As you can see, this is a highly algorithmic process that is based entirely on the learned statistics of word sequences.

Judging personhood

Now we are in a position to reflect on whether ChatGPT and similar AI systems can be described as conscious persons. It is worth noting at the outset that the algorithm has had no conscious experience of what is expressed by any of the word sequences in its training data set. The word ‘apple’ will no doubt occur millions of times in the data, but it has neither seen nor tasted one. I think that rules out the possibility of the algorithm experiencing ‘qualia’ or P-consciousness. And as the ‘hard problem of consciousness’ dictates, like humans the algorithm cannot access the subjective experience of other people eating apples and smelling roses, even after processing millions of descriptions of such experiences. Algorithms are about function not experience.

Some might argue that all the ‘knowledge’ it has gained from processing millions of sentences about apples might give it some kind of representational A-consciousness (A-Consciousness describes the representation of something to the conscious awareness of the person). The algorithm certainly does have internal representations of apples and of the many ways in which they have been described in its data. But these algorithms are processes that run on material things (chips, computers), and, as we have seen, there are reasons for being somewhat sceptical of the claim that consciousness is a property of matter or material processes.

According to the very limited survey we had here of the Western understanding of ‘personhood’, algorithms like ChatGPT are not persons as we ordinarily think of them. Personhood is commonly thought to something that an agent has that is capable of being in relationship with other agents. These relationships often include the capacity of the agents involved to communicate with each other. Whilst it appears that ChatGPT can appear to engage in written communication with people, based on our rudimentary coverage of how this algorithm works, it is clear that the algorithm is not intending to communicate with its users. Neither is it seeking to be friendly or empathetic. It is just spewing out highly probable sequences of words. From a theological perspective, personhood presumes spirit, which is also not a property of any AI algorithm.

Algorithms may behave in very realistic, humanlike ways. Yet that’s a long way from saying they are conscious or could be described as persons in the same way as we are. They seem clever, but they are not the same as us.