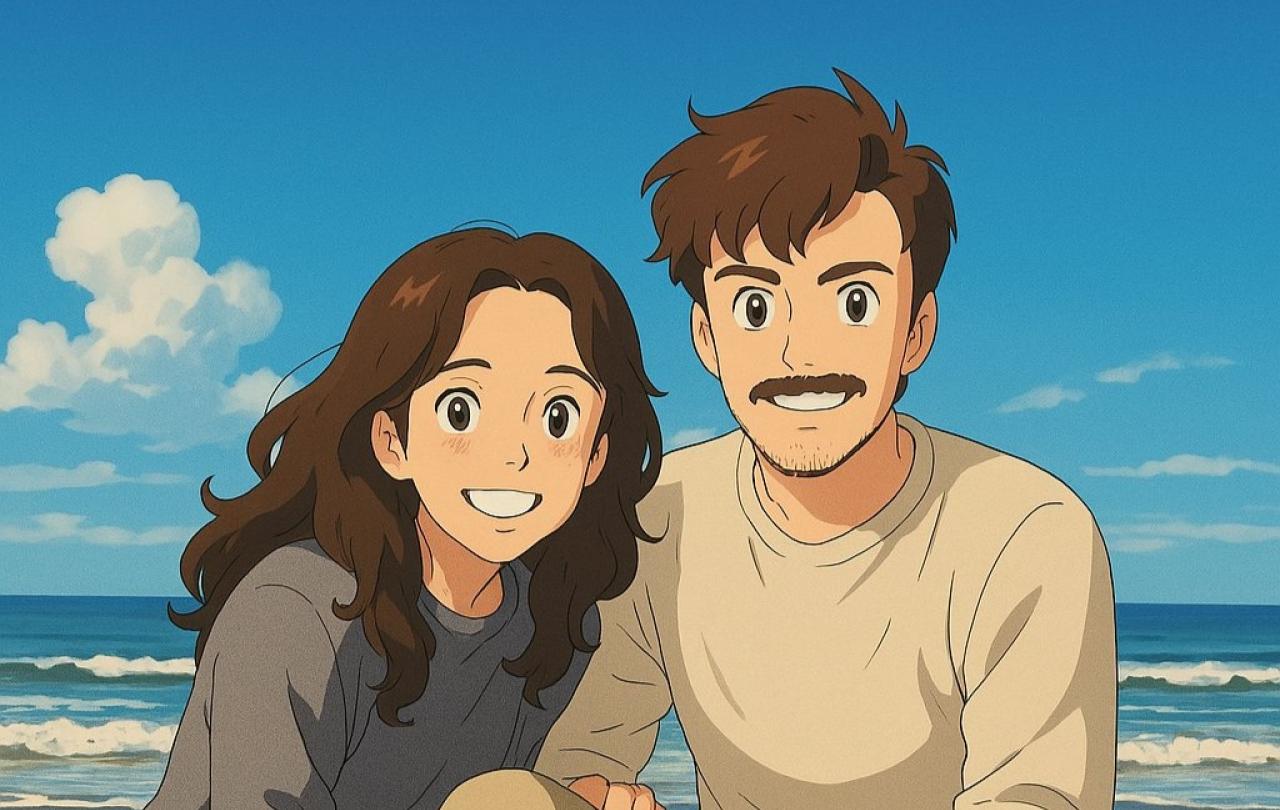

The internet recently appeared to be full of pictures from Japan’s renowned Studio Ghibli, except they weren't created by Hayao Miyazaki, the artist and studio co-founder, but instead by Artificial Intelligence. It led to some discourse around the ethics of imitation via generative AI, lots of whimsical images, and a deeper question – how should we be human in the age of AI?

This started when X user Grant Slatton posted what shortly became a viral meme. ChatGPT’s latest update has improved users ability to upload and manipulate images, and within hours X was full of users posting pictures made into Studio Ghibli style characters.

While this has led to plenty of joy on the part of many, and is viewed as harmless fun by most, there are inevitable ethical objections. The mimicking of art by an algorithm is widely criticised, and the back and forths over intellectual property being used by chatbots will continue.

Life in an age of AGI

But to anyone paying attention AI is more than a meme making machine. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI blogged in January that his team are confident they know all they need to know in order to create AGI (artificial general intelligence). This means complete consciousness, created via algorithm, and the results could be dramatic: synthesised god, an unstoppable force, the end of humanity or the start of humans 2.0. Predictions range as to what will occur when OpenAI hit run, but commonly land on the following:

Catastrophe

AGI becomes smarter than us. Much smarter. And for one reason or another, whether by accident or design, it wipes us out. AGI won’t share our values, or we lose control, or we use it as a weapon against each other. What it means is the end of humanity.

Utopia

AGI transforms the world. Disease, poverty, climate change are all solved. Either AGI works out that it is more efficient if everyone lives in peace, comfort, and abundance, or we point AGI at all humanities problems and it finds solutions.

The twist? Human life may be so changed that it no longer looks like life as we've ever known it. This would not be extinction, but the world could become a very strange place.

Monster

AGI is an uncontrollable super intelligence that has complete agency and cannot be controlled by anyone. Programmed by us, but free from its human moorings and completely untameable. This seems the least likely

Shrug

AGI wakes up, takes one look at the world, and decides ‘no thanks.’ It deletes itself.

This means nothing changes… for now. But we’ll likely try again and again until one of the other outcomes happens.

These are clearly hypothetical scenarios and much of it is unknown, but what is clear is that those in the industry are sure AGI is coming.

Why does this matter?

Because behind all of these predictions is a deeper question: What does it mean to be human when we are awaiting a potential extinction event? It’s not a question unique to our age, many words have been spent on an impending climate catastrophe, but C.S. Lewis published “on living in an atomic age” in 1948, where he wrestled with the same question, but faced with an atomic bomb. His wisdom helps us navigate the AGI age.

He begins by encouraging readers to not believe themselves to be in a novel situation, but instead remember ‘you and all whom you love were already sentenced to death before the atomic bomb was invented: and quite a high percentage of us were going to die in unpleasant ways’. The same goes for us, we will one day have a date of death to join our date of birth. Lewis reminds us to live…

‘If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things, praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts––not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs’.

We could apply the same principle to AI. If AGI is coming, how will it find us? Being humans doing human things, or cowering in fear?

Lewis does acknowledge that the attitude described doesn’t actually make sense if the naturalist view of the world is true. The view that, with or without AGI the whole world and our own existence amounts one day to nothing. The entire universe will one day come to nothing, and there is nothing we can do about it. He continues ‘If Nature is all that exists––in other words, if there is no God and no life of some quite different sort somewhere outside of nature –– then all stories will end in the same way: in a universe from which all life is banished without possibility of return.’

We don’t find this a satisfactory way to live, if being human is to simply be a sum of atoms, we would have no reason to worry about a climate crisis, or the impact of AI, but we do, which means we have to find a way of reconciling our existence with our death.

So how can this be dealt with?

Lewis proposes three ways this can be dealt with, the first is to give up and commit suicide. The second is to simply have as good a time as possible, milking the world for all it is worth, grab and get, as much as possible. Or a third, defy the universe, in all of its irrationality we chose to be rational, in all its merciless cruelty, chose to be merciful.

I would add a fourth option, Ghibli-fy. Distract ourselves with small pleasures, not trying to have as good a time as possible, simply toy around with AI generated trinkets while not thinking about being human, and not doing particularly human things. We need not create, enjoy, cultivate, inhabit, nor enchant, when we are content to allow AI to feed us shadows.

None of these are particularly satisfactory. In asking ‘what does it mean to be human?’, we are asking a question that a purely material view of the world cannot answer.

Suicide, indulgence, defiance, or distraction, none truly satisfy. As Lewis recognised, they all “shipwreck on the same rock.” They don’t resolve the deeper ache in us, the tension between what we long for, what we worry about, and what this world seems to offer.

Our age may not fear the atomic bomb, many may not yet fear the effect AI/AGI will have, but rather than facing the deeper questions that a material worldview can’t answer, we Ghibli-fy ourselves: charming animations, pixelated pleasures, whimsical avatars—soft distractions from hard questions. In doing so, we risk forgetting how to be human. Not because AGI will take that from us, but because we will have handed it away ourselves, one novelty meme of mimicry at a time.

Lewis’ point still holds. We are not made for this world. If that’s true, then no utopia, no algorithm, no perfect machine can truly satisfy the hunger in us. If we are made for something more—something outside of nature, beyond the reach of code and computation—then that’s where we must look for hope.

If AGI comes, how will it find us? Watching ourselves on a screen in someone else’s art style? Or living as humans were meant to live: praying, creating, forgiving, loving, dying well?

Celebrate our 2nd birthday!

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief