“Everybody’s capable of doing wild things,” says artist Peter Howson, scratching his head as he looks pensively over his paintings. He is talking about the events of his youth and how experiences of trauma, addiction and childhood bullying have influenced the way he paints the misfits, non-conformists and the overlooked.

Howson is one of those rare breeds of artist who garners both public adoration and critical acclaim, an achievement celebrated in his recent retrospective at Edinburgh City Art Centre, an ambitious show spanning four floors and four decades of the painter’s career.

I asked curator, David Patterson why Howson’s work continues to draw public interest. “People can see in every brush stroke how he pours his heart and soul into it,” he replies. “A lot of people are commenting on his honesty. He’s brutally honest and speaks what he feels in his heart.”

Howson rose to public attention shortly after his graduation from Glasgow School of Art in the 1980s with a public commission for a series of wall murals for the Feltham Community Association in London. He became known for his visceral depictions of men caught in contradictory states often painted in monumental scale with his particular style of raw, fleshy realism, an approach influenced by his interest in German Expressionism. It was his tutor, Alexander Moffatt who first introduced Howson to the work of Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, their brutal exposition of the German bourgeoises clearly making an early impact. From the hulking boxers and football hooligans of his early career to the bullish vulnerability of soldiers currently fighting in the Ukraine war, his characters are rendered with a raw realism, matched only by the brutal honesty of the artist himself.

People misunderstand the meaning: they think that I’m making (those men) into heroes, when it’s not that at all.

Howson was part of a group of male figurative painters known as the New Glasgow Boys, alongside Adrian Wiszniewski, Ken Currie and Steven Campbell, who studied at the Glasgow School of Art at a similar time in the 1980s. Later artists such as Jenny Saville and Alison Watt would continue the Scottish figurative tradition.

It might be easy to misread his early work in particular as a kind of ode to masculine swagger but when Howson speaks of his work it becomes clear his intentions are more to dispel such toxic masculinity. “I was bullied a lot at school,” he reflects. “I felt so emasculated when I was young, I tried to build myself up: I became a bouncer and wanted to exact revenge on my bullies and I joined the army. All these things that are really not me. People misunderstand the meaning: they think that I’m making (those men) into heroes, when it’s not that at all. It’s a contradiction: I’m trying to get power into my work at the same time as taking the mickey. But some of the Bosnian work is my freest.”

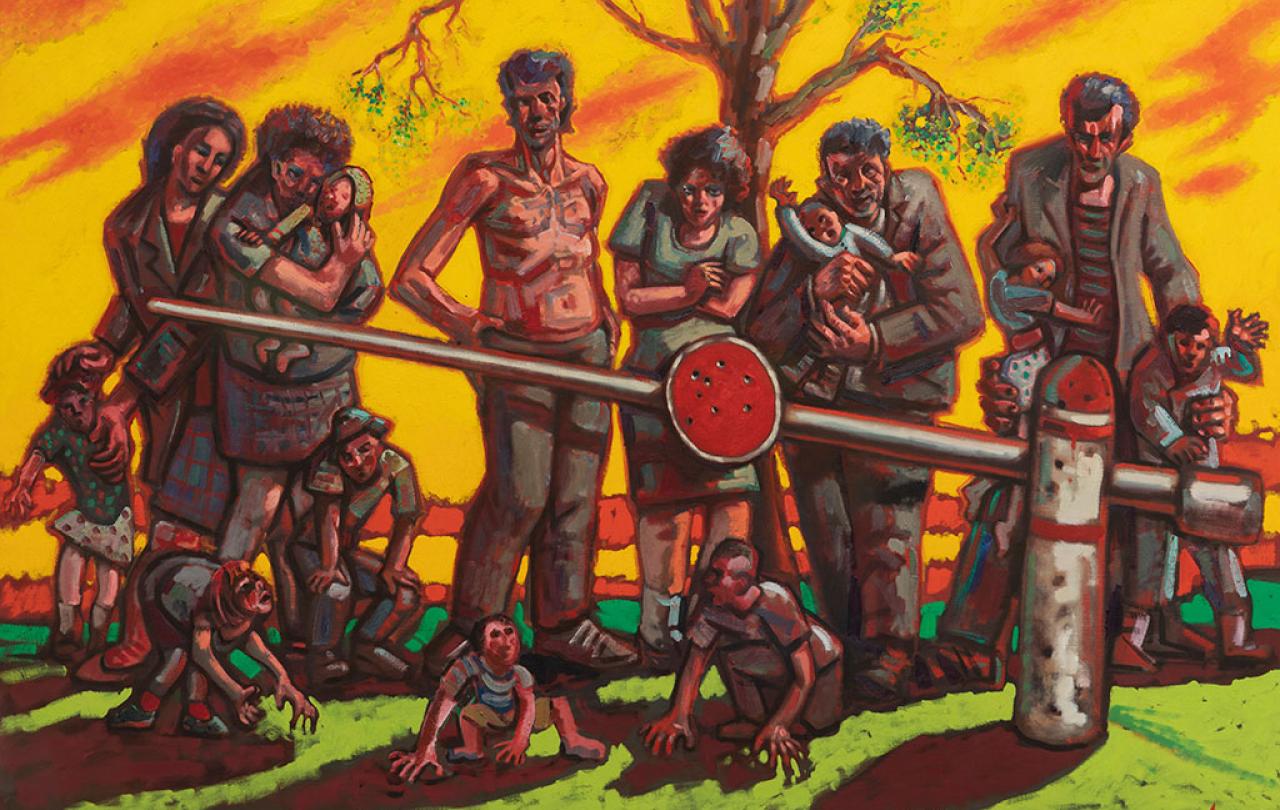

In 1993 Howson was appointed as official war artist to the Bosnian conflict where he witnessed first-hand the atrocities of conflict. This work culminated in a solo exhibition at London’s Imperial War Museum with some of the most harrowing and empathetic works of his career so far. Barrier Sunset, painted in 1995, shows a line of Bosnian refugees, emaciated and restrained by a blockade that bars entry to safe land. Behind them, a burning sky speaks to the ravages of war.

Howson is an artist who wears his past on his sleeve, speaking openly about his autism, childhood traumas, recovery from addiction and unnerving experiences serving in the army which he describes as “hell on earth”. Rather than dismissing these traumatic experiences, Howson finds way to manifest them in paint, a process that demonstrates profound empathy with his subjects, both villain and victim.

“You’re always walking a tightrope and I always say I’m walking on the edge of the cliff,” says Howson as he reflects on the influence of traumatic memories. “The trick is not to fall off. But you can go to the edge and look over into the abyss and the abyss is frightening.” Howson takes us to the abyss and brings us back again. Like Dante, a key influence on the artist, Howson doesn’t shy away from the more macabre, morbid and sinister subjects of the human experience yet refuses wallow. His recent ink paintings depict the effects of corona virus and atrocities of the war in Ukraine. Rendered with biblical intensity, bodies writhe in a mass of human flesh pulling and straining as in battle or torment.

His faith is as sincere as his painting, neither dogmatic or didactic, worn on his sleeve along with his experiences of trauma and addiction

Unusually in British art, Howson also speaks openly about his faith, having converted to Christianity later in life. Indeed, a whole floor of the exhibition is dedicated to his religious paintings. “There’s a part of me that wants that peace” he says. “It’s why I’m not frightened of the death thing. The real life is yet to come.” Howson acknowledges the unusual nature of his belief, not least in an art world where sincere religious faith is something of a novelty.

“There’s hardly anyone believes these days but I don’t care if I’m wrong anyway because I’ll never know it anyway.” Even his faith is expressed with honest cynicism. “Religion in art is unfashionable,” he says yet Howson seems unfazed by fashions. His faith is as sincere as his painting, neither dogmatic or didactic, worn on his sleeve along with his experiences of trauma and addiction.

Prophecy

2016; oil on canvas; 183.5 x 245cm; private collection; © the artist; photograph Antonio Parente.

This exhibition laments the broken nature of our world yet offers glimpses of hope in human empathy, compassion and ultimately in a redemptive God. In this way Howson describes his painting as “a warning of what’s to come”. Howson refuses to be defined by his traumatic past and it seems evident he now sees the world through the lens of his Christianity, a perspective that clearly defines his understanding of human nature, masculinity and redemption. Whilst we might consider Howson a chronicler of our times his painting are more than reportage. He looks into the very soul of humanity, finding hope in the horror, making visible the invisible and giving voice to the unheard.