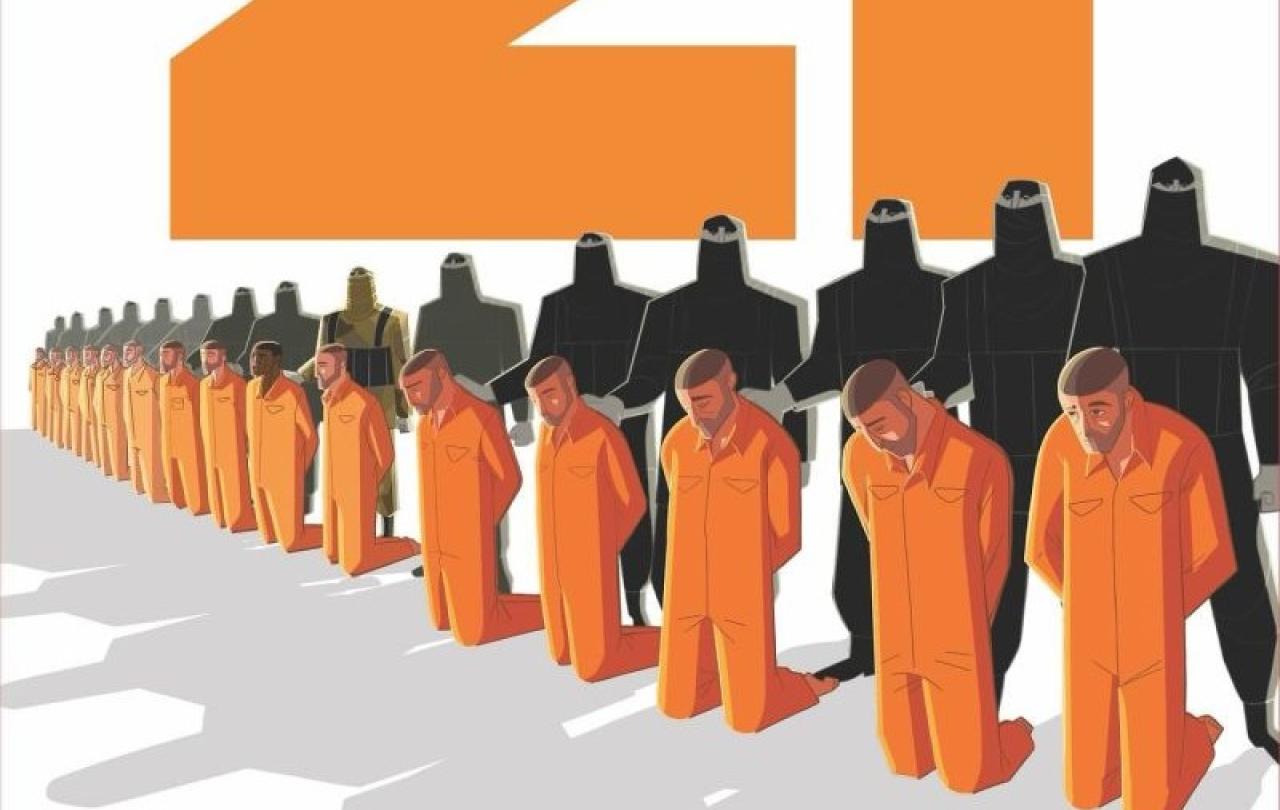

In 2015, 21 men were kidnapped, tortured, and eventually killed by ISIS. Twenty of those men were Coptic (Egyptian) and one, Matthew, was Ghanian. They were all Christians. And that is why they were killed.

Over the past decade, the story of their martyrdom has been widely told. And yet, the only piece of visual storytelling that existed was the propaganda video, filmed and released by ISIS. A film that was intended to scare the world and dehumanize the men, a film that glorified violence and hatred.

We’ve known the story of the men’s execution, but we’ve only known it as told by their executioners.

That’s no longer the case. On 15 February 2025, ten years since their death, the story of the 21 is being re-told by a team of over seventy artists from 24 countries, directed by Tod Polson, and in collaboration with the global Coptic community. The short film, The 21, will premiere on the anniversary of the men’s death and be featured at film festivals throughout 2025.

We knew a story, now we’re hearing their story.

I was able to talk through the details, how and why this short-film was made, with one of its producers – Mandi Hart of MORE Productions. After watching the film a handful of times, and needing ten minutes to recover after every viewing, I had lots to ask Mandi. Firstly, I wanted to know all about the visual aesthetic.

This film is animated, which feels like both a defiance and a kindness. It’s a defiant choice because it ensures that this film stands in contrast to the film that was released ten years ago, where pure terror was the only story-telling objective. Nothing about this film is reminiscent of that one. And that’s a kindness to us, the audience. We’re not totally spared, however, as carefully selected moments of the original footage are woven into this short film, reminding us that these men – the ones who were killed and the ones who did the killing - were as real as you and I. But, on the whole, we’re spared the worst of the horror. As Mandi noted,

‘animation allows your imagination to fill in the gaps. It’s just as powerful a form of story-telling, if not more so’.

Mandi’s right. This film will stop you in your tracks. More than anything, though, the visual aesthetic is an ode to the men who were lost and the community they belong to.

Director, Tod Polson, travelled to Egypt to meet with Coptic iconographers and learn about the intricate ways they communicate in symbolism, iconography and art. Mandi told me that even details as subtle as the width of a line used or the placement of the eyes on a human face have deep wells of meaning held within them. Polson also visited Minya, the Egyptian region that was home to many of the martyrs, and gathered inspiration from the church that was built there in their honour. The film’s aesthetic derives from all of this, it’s drawn in alignment with what Polson learnt. In other words, the story is told in the language of the martyrs. Through the work of the seventy plus artists, this story is weaved into the story – the Coptic story, the Christian story. It’s rooted and yet timeless, a decade old and yet ancient.

For the men standing on the beach, an assassin standing behind them, the veil between the seen and unseen was incredibly thin.

The film is a masterclass in learning the language of the ones to whom you’re paying tribute. The artists have honoured the martyrs on their own terms and according to their own story. It’s a special thing.

It’s also a challenging thing. It’s a harrowing event, after all. It feels as though, through this film, we’re brought closer to the torture the men endured, given details that the mainstream media left unreported. Details such as, the floor they were forced to sleep on was continuously pumped with water, the relentless taunting and manual labour, the beatings, the fact that they were actually put in orange boiler suits, taken to the beach, and filmed three times. It was on the third time that they didn’t return.

40 days, that’s how long the twenty-one were held for.

960 hours.

57,600 minutes.

3,456,000 seconds.

The longevity and intensity of the torture is nearly impossible to fathom. The fear they must have felt is mostly unimaginable. Mandi mentioned that she was probed by a continual set of questions as she studied this story, these men, and those days. The questions went along the lines of: what would she be willing to die for? Would she be brave enough to stand her ground? Would she be faithful to what she believes to be true? Would she choose a life without Jesus or a death because of him? It’s a hypothetical set of questions for Mandi, and for me too. But not for the 21 men.

Finally, I wanted to ask Mandi about the inclusion of supernatural facets of the story – the improvable, un-fact-check-able stuff. If I was to be brave, I guess I would say the truest stuff. The way the heavens seem to open, rage, and weep; the subtle appearances of Jesus’s scarred and bloody feet; the mention of a prayer-fuelled earthquake in the prison; the glimpses of a supernatural army guarding the 21 men as they walked to their death. It’s quite weep-worthy, really. The closer these men get to their execution, the brighter and more vivid the ‘unseen’ becomes.

Yet, it feels like quite a brave storytelling choice, to meld the provable with the improvable facts of the story.

‘Only to us’, Mandi reminded me. ‘we, the cultural West, struggle with the supernatural stuff. It’s an affront to the ‘rational’. But we’re the minority. The majority, who have less cultural power, they don’t struggle with this stuff at all... ’

This led us to speak about the seen and the unseen elements of reality, how – as Christians – we believe that all that we see is not all that there is. In fact, the things that cannot be seen are the realest things. And how, for the men standing on the beach, an assassin standing behind them, the veil between the seen and unseen was incredibly thin. It’s comfort that often makes the veil thicken out, Mandi reminded me, it’s the left hemisphere of our brains that tells us that all that we see is all that there is. When our safety and comfort are stripped away, what happens? For the twenty-one martyrs, it seems as though the veil became thread bare. As Mandi quite remarkably noted, ‘the human soul knows more than the mind is comfortable admitting’.

The 21 is a short film about death, the death of 21 innocent men. It’s important that we give these men our attention, look them in the eye and weep with those who weep. But I think, in a way, this short film also tells the story of life. Life after death, life that death doesn’t put an end to. Life that confounds death, even. And in that way, this film tells both a particular story and a universal one, both their story and the story – the Christian story.

Watch the trailer

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief