The Israel-Gaza war and the recent row between the church and the UK government over asylum seekers don’t seem on the surface to have much to do with each other. But they do have a common denominator: Iran.

Iran may not have directly sponsored Hamas’ infamous attacks on Israel on October 7th but without Iranian support for Hamas, it is unthinkable that they would have happened. Iran remains on the list of those countries who sponsor terrorist organisations across the Middle East, such as the Houthis in Yemen, and are widely regarded as a force for instability and undermining democracy across the region.

It is also one of the most repressive nations on earth. It counts in the top ten of countries where freedom of religion or belief are restricted. According to the Open Doors’ World Watch List, list, Iran is the ninth most dangerous country to be a Christian in 2024, just behind Sudan and ahead of Afghanistan. With 1.2 million Christians in the country, they make up just 1.4 per cent of Iran’s population, and yet, they are considered to be a risk to national security and a means by which the West is seeking to undermine the Iranian government. This inevitably makes life incredibly hard for the Christians who call Iran home; to be a recognised Christian means to live your life as a second-class citizen, under constant surveillance, and enduring endless discrimination.

Given that Iran is hardly a friend of the UK, the USA and its allies, you might have thought western governments would do all they could to support people seeking to escape the country, or a movement that draws people away from the influence of the mullahs. Which makes the attack on asylum seekers seeking baptism in UK churches all the more perplexing.

Over the past week, Seen & Unseen has spoken to several Iranian Christians in the UK. These are definitely not bogus Christians. Some came to Christianity in Iran after a Muslim upbringing. Others were born into the small Christian community in Iran. Some are training to be ordained in the Church of England, and many of them have been imprisoned for their faith in Iran before coming to the UK.

“The persecution that Christians are facing in Iran is absolutely real. Does that mean that some of them are leaving the country? Yes. I had to. I’m here. I had to leave my home.”

One man, Mehdi (his name has been changed to protect his identity) became a Christian in Iran at the age of 18. His older brother converted to the new faith first and Mehdi, having seen his big brother struggling with violence, anger, depression and drugs, was curious about the complete and immediate change in his brother’s life. That curiosity led him to believe in Jesus. It became immediately obvious to these two brothers that their new faith was going to make their life complicated; and at the age of 20 and 26, they found themselves being arrested for the first time.

He explains what drew him, and many others to Christianity. “It’s the same for many Iranians. There were people around us who are who were, and still are, dealing with lots of difficulties because of the economic situation, because of the oppression and corruption of the government. It feels like there’s no hope, no solution. The only solution can be found in the hidden places. It’s Jesus. He is the hope of a new life.”

He tells us how Iran sees Christians: “They believe that Christianity is a weapon of Western countries, with a long-term plan to convert Islamic countries like Iran so that they can alter the culture and take the power.”

After years in prison, much of it in solitary confinement in degrading conditions and yet more threats from the authorities, he was forced to leave Iran. He is now living in the UK with his wife, and at the midway point in his training to be a priest.

We wanted to know what he thought of the comments concerning the church and ‘bogus asylum claims’:

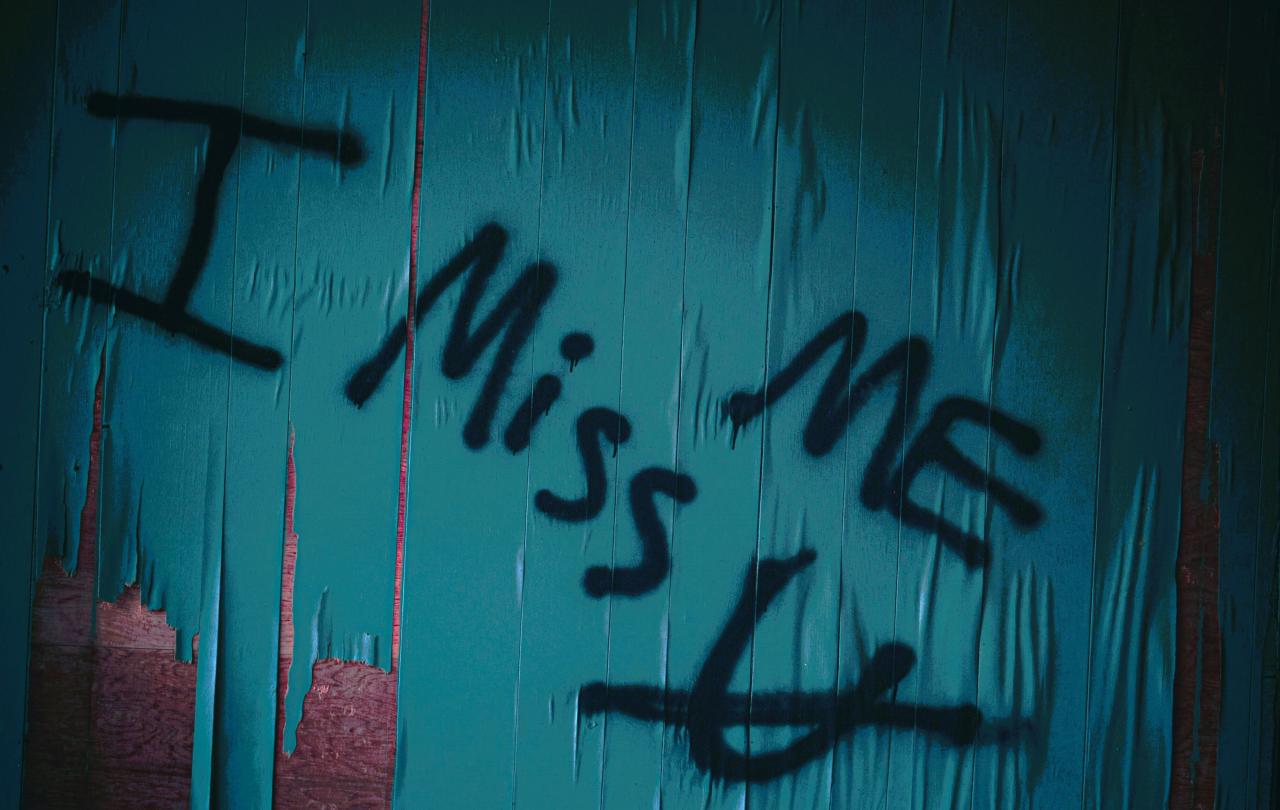

“The violation of human rights, the right to both free speech and freedom of belief, in Iran is real, it’s true, it’s happening. The persecution that Christians are facing in Iran is absolutely real. Does that mean that some of them are leaving the country? Yes. I had to. I’m here. I had to leave my home. And there aren’t enough legal routes, there aren’t enough ways to seek asylum in countries like the UK.

So, it’s true that Christians are leaving Iran. I’m one of them. And I was incredibly lucky, I got here safely and securely.”

Another convert, Hassan (also a false name to protect identity) while at home in Iran, went though the usual teenage angst, wondering about his place in the world, and whether God really exists. He delved into Islamic theology but says it left him ‘feeling empty’.

After a few months of praying that God would somehow reveal himself, Hassan had a dream of a figure on a cross. This was the beginning of a journey that led him to faith in Jesus Christ. Hassan talks about his experience with the immigration system: “It’s hard for the Home Office, but the church has an important role to play – to support the people who have been persecuted, who have never before had a place to learn about or worship God. Those who have never had the freedom to express their faith, or live in their faith.”

They are habitually religious people, so are not naturally drawn to atheism or agnosticism. On arriving in the UK, which they assume to be a Christian country, they naturally want to explore the faith of the country that they have arrived in.

An Iranian refugee Darbina, unlike the others, was born as a Christian into a Christian family. Yet she speaks of how Christians are persecuted in Iran. She says they are treated like second class citizens, unable to sell food because they are regarded as unclean, unable to enter many professions because they are Christian. She describes the open surveillance of Christians. Her father, a pastor, was imprisoned for ‘acting against national security’ by organising small groups and illegal gatherings. Eventually Daria herself was imprisoned for a year. She experienced degrading treatment as a woman in a predominantly male prison, and frequently had to listen to the torture of others.

There is another common story. Many Iranians leave Iran not yet as Christians, but seeking a better life from an economically depressed nation and disillusioned with the form of Shia Islam found in the country. They are habitually religious people, so are not naturally drawn to atheism or agnosticism. On arriving in the UK, which they assume to be a Christian country, they naturally want to explore the faith of the country that they have arrived in, even when they find the UK church more lukewarm than they expected. Of course, there are a number of Iranian Christians already in the UK such as Mehdi, Nasir and Daria, ready to help them discover a faith which has become vital to them. This would seem a much more common explanation of Iranian Christians wanting baptism, then simply a cynical attempt to manipulate the asylum system.

Of course, there are Iranian and migrants from other countries claiming false conversion as a means of advancing their case for asylum. No-one doubts that. Yet the problem has been exaggerated. A recent Times report found that since January 2023 only 28 cases were heard at the Upper Tribunal Court in which a claimant cited conversion to Christianity as a reason to be granted asylum – in other words, just one per cent of cases heard. And of those 28, seven appeals were approved, 13 were dismissed and new hearings were ordered in eight cases. Hardly an ‘industrial scale’ operation. Yet there is a great deal of evidence of numerous people like those we spoke to, who have genuinely converted to Christianity, either in Iran itself, or in the west.

More significant than the comparatively small number of fake claims, is evidence of a genuine religious revival amongst Iranian Muslims, drawn to Christianity as a more attractive option than the oppressive form of Islam they find in their homeland. Attacks on Iranian and other migrants, with the implication that all Iranians seeking conversion are bogus, or at least feeding suspicion of such claims to conversion is undermining exactly the kind of movement that you would have thought that the British government would be wanting to encourage.

If there is something of a spiritual revival taking place amongst Iranian Muslims then this should be something to be celebrated rather than penalised or tarred with the brush of deception. We owe it to these people who have risked their lives to find a better way of living and believing.