Were there signs I missed?

Why couldn’t they stay for me?

Could I have done something?

These and a million other questions fill the minds of those who lose a loved one to suicide - and there are no easy answers.

Suicide evokes a particular loss which can torment those left behind with grief and guilt. With suicide rates reaching a twenty-five-year high, too many people are living with these unanswerable questions.

At the heart of many of these questions is the stigma which still surrounds suicide; it was only eighty years ago that suicide was still a crime and much of the condemnatory thinking remains.

People still believe that suicide is somehow selfish, that it’s the reserve of only those most severely affected by mental illness or that nothing can stop someone from taking their own life if they’re considering it.

The truth is far more complex and, thankfully, far more hopeful because whilst suicide is complex - it can be prevented.

A heartbreaking 1 in 15 people will attempt to take their own life - and most will survive, with trauma, yes but also with the opportunity to build a life that they can bear.

Suicide prevention involves the whole of society. From government, charities, families and friends, it has to begin with shattering the myths that perpetuate the stigma. And, we need to begin by changing the language we use: Suicide is not a crime that is committed so people don’t commit suicide, they die by suicide and by moving away from the language of committing we can begin to accept that suicide is no-one’s fault - it’s a tragedy.

Suicide is not selfish; for many people in the depths of suicidality, they believe that they are relieving their loved ones from a burden, and it can affect anyone - including those with no history of mental ill-health.

Many have believed in the past that once someone has decided to take their own life, there is nothing that can be done to stop them, but suicide is preventable with openness and honesty.

A heartbreaking 1 in 15 people will attempt to take their own life - and most will survive, with trauma, yes but also with the opportunity to build a life that they can bear, but they need help to do so.

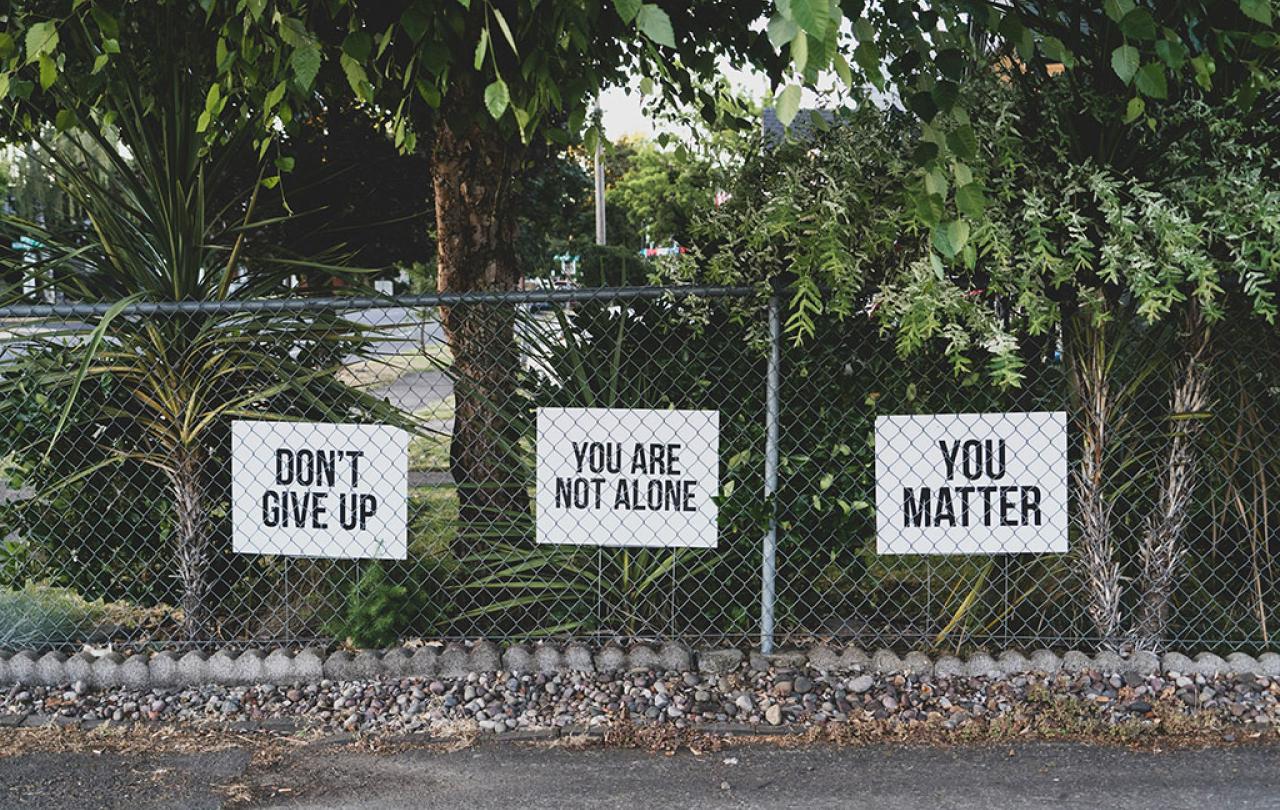

We each have a role by reaching out with kindness and creating sanctuaries.

As a teenager, I twice attempted to take my own life and I’ve lived with thoughts of suicide for almost twenty years, but I am still here - in large part due to the kindness of others as they held hope for me when I could not manage it alone.

Perhaps strangely, the place I wanted to be the most in the wake of my attempt was church; it was the place I felt the safest and I wanted to be in a place where I could cry and let out my conflicted and confused feelings to God because I felt there was no-one that could understand what I was going through. I remembered the character of Elijah in the Bible who begged God for death and was met with God encouraging rest, nourishment and the opportunity to pour his heart out. It was what he needed in his darkest hour, and it was what I needed in mine.

We cannot take on the role of mental health professionals - and neither should we - but we can be prepared to hear the hardest words and to listen to someone’s thoughts of suicide because research shows us that allowing people to give voice to their despair makes space for hope to grow.

When people are struggling with thoughts of suicide or trying to navigate the aftermath of a suicide attempt, we each have a role by reaching out with kindness and creating sanctuaries; safe spaces for those who are struggling to express their despair and receive compassion. It might look like dropping around a meal, listening to them pour their heart out, advocating for them with mental health professionals or offering childcare or running errands.

We can all play our part in changing the culture around suicide with language, care and holding hope for those who feel that all hope is lost.