A little while ago I went for a health check. They took a blood test, weighed me on the scales, poked me around a bit. Soon afterwards, I got a printout of my general health. It told me that my blood pressure and liver function was pretty good, but I ought to watch my cholesterol, my calcium levels could be a bit higher, and my folate result was not great (whatever that is).

It told me a lot about my physical health. What it didn’t tell me was anything useful about my spiritual and moral wellbeing. I began to wonder where I could get a spiritual health check? Is there a way of telling whether I am in danger of diseases that might affect my soul rather than my body?

As it happens, the Christian church has long had a spiritual health check - a kind of ticklist for spiritual and mental wellbeing – it’s called the Seven Deadly Sins. And over the next few weeks, here on Seen & Unseen, we’ll be running a series on it – think of it as a chance to check out your own spiritual wellbeing.

Of course, the word ‘Sin’ has a chequered past. Peccatio, Pèche, Sünde, Sin – whatever language it came in, it was once a terrifying word – a word that struck fear into the heart of almost every European. It had the same kind of emotional effect as words like ‘Nazi’, or ‘cancer’ do for us today. It was something you wanted to avoid at all costs, something dreadful and dangerous.

Now, it has changed from a rottweiler into a poodle. ‘Sin’ has been calmed down, domesticated, neutered. The word is now usually spoken with a smirk, or a heavy dose of irony. Describing something as ‘sinful’ usually means you think it is naughty but nice, or even seductive. We get perfumes called ‘My Sin’, or even a bakery called ‘Sinful Cakes’. Po-faced people who denounce something as ‘sinful’ seem to just want to stop other people enjoying themselves.

They waged a constant, subtle and undermining war against the inner self – they were the deadly enemy of the soul.

Yet there were reasons why the word ‘sin’ had such a ghastly aura about it in the past. Sin was not harmless transgression of some random moral code invented by repressed and frustrated medieval clerics. For our ancestors, ‘sin’ described a pattern of life that was quite simply destructive. Each of the seven deadly sins were a sign of spiritual poor health just like a raised PSI count might be a sign of prostate cancer, high blood pressure a sign of the risk of a heart attack and so on. Sins like greed, anger, lust and pride could destroy families, friendships, happiness, peace of mind, innocence, love, security, nature, and most importantly, our bond to our Creator. They wrenched us out of our proper place in the world, which is why it’s worth knowing whether you’re suffering from them or not.

A passage in the Bible talks of “sinful desires, which wage war against the soul.” That captures it well. These impulses or patterns of behaviour were not just arbitrarily wrong, but self-destructive. They waged a constant, subtle and undermining war against the inner self – they were the deadly enemy of the soul. Sin was a like a virus that got into everything, so that although life carried on, it never quite worked in the way you felt it ought to. Life always had that grit in the oyster, the nagging soreness of a shoe that doesn’t fit, the reminder of a dark secret that wouldn’t go away.

In many people’s minds, ‘sin’ means simply ‘breaking the rules or the law’. The difficulty with this idea is that it fails to get to the heart of the issue. An insistence on rules alone is often a sign of a shrivelled, arid moral vision. It’s what makes disapproving busybodies and prudes. Laws exist to protect things that are more important than laws, like human lives, families, marriages, reputations, communities and peace. They are not ends in themselves. Rules and laws are vital for the protection of goodness, but do not itself go to the heart of goodness – they simply try to ensure its survival.

Life would be simple if things that were bad for us were ugly and things good for us were beautiful.

One traditional way of thinking about sin was to classify it into types. Our ancestors were shrewd enough to know they needed to know their enemy. The idea of the ‘Seven Deadly Sins’ emerged from the early centuries of the Church as a neat way of remembering the some of the chief ways in which this deadly pattern of behaviour manifested itself.

A glance through the traditional list of the seven deadly sins raises an obvious issue for anyone with any sense of contemporary life and morals: these are not the ones we’d identify as the chief causes of evil in our world. If anything, our culture tends to admire these qualities, not avoid them. Lust is a sign of a healthy sexual appetite, Pride a perfectly valid pleasure in our own achievements, and Greed an essential motor for the economy. Lust, envy and gluttony sell porn websites, cars and food, so naturally there are powerful forces dedicated to encouraging these habits to grow as rampant as possible in our souls and societies.

Of course, our forebears were not all as innocent as we might think. Of course they didn’t all detest sin because it has always carried a very real and powerful attraction. And unless we grasp this, we will never understand it. Life would be simple if things that were bad for us were ugly and things good for us were beautiful. But life isn’t like that. As the great St Augustine said of his own younger tendency to steal just for the sake of it: “It was foul, and I loved it”.

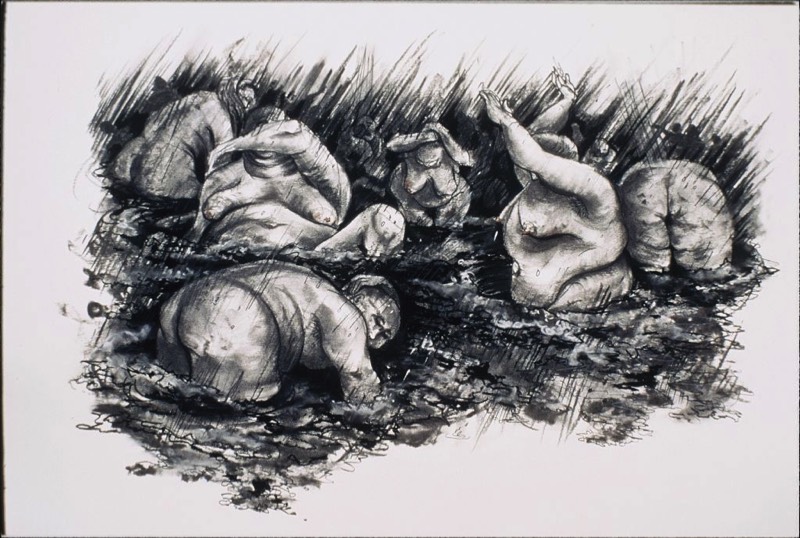

The great works that have dealt with sin in the past had a simple aim, to uncover the ugliness of sin, and unmask the veneer of attractiveness that it wears. Dante’s great Divine Comedy did it by showing what these patterns of behaviour led to. It showed how each received its fitting punishment in a vision of such elegant symmetry that it seemed so obvious. In Dante’s imaginary hell, the angry are condemned to fight each other for eternity; the slothful or indolent are condemned to running constantly and breathlessly; gluttons are made to lie in mud, exposed to constant rain and hail just like pigs, and end up eating rats, toads and snakes, as a parody of their excessive greed.

Illustration by Jennifer Strange Keller

Yet strangely, each sin always has at its heart something good. Medieval artistic depictions of sins portrayed them as misshapen and deformed versions of some good quality. The reason is not hard to find. Lust takes the delights to be found in sexual desire and satisfaction and distorts it into an uncontrollable, damaging enslavement. Gluttony twists the pleasures of succulent roast beef and a glass of dark red Beaujolais and turns them into bloated, sickly over-consumption.

There is always something of the grotesque about sin. In old fairgrounds, there was always one stall where you would place yourself in front of odd-shaped mirrors, which would exaggerate parts of your body and shrink others. The result was on the one hand funny but at the same time, slightly frightening. Sin does the same thing. It takes something beautiful and makes it ugly by twisting it out of shape, so that it bears enough resemblance to the original to retain its attraction, but when seen in its full light, is as ugly as… well, sin. On one level, it’s funny. Most of our jokes revolve around the grotesque - things out of place, misshapen, strange. Yet there is a dark side as well and it is that that these medieval imaginative poems tried to unveil. Theologian Cornelius Plantinga says: “a sinful life is a partly depressing, partly ludicrous caricature of genuine human life.”

A woman in a hall of mirrors, circa 1935.

Although it can seem a monstrous and terrifying power that threatens to overwhelm everything, in the end, evil can only ever distort something that is at its heart good. Evil cannot create anything, it simply twists, caricatures, or destroys. Sin is always a parody, a type of behaviour that often looks vaguely like goodness, and often likes to pretend it is, and it sometimes takes some moral and spiritual discernment to tell the difference. Yet a difference there surely is, and the ability to tell good from evil is a real sign of human and personal maturity. But the reason why it is often difficult to tell is that sin always has at its heart something good. A fit of temper against a brother or sister or child usually justifies itself by the behaviour that provoked it in the first place, which probably was out of order; jealousy or envy persuades itself that it is really proper outrage against the deep injustice that has given to someone else what I really deserve.

This means of course that however monstrous sin or evil are, in the Christian view of the world, they are ultimately trivial and pathetic when compared to real goodness. St Augustine struggled all his life to understand the nature of malevolence. Towards the end of that life, the reality of evil began to recede from his attention, to be replaced by something much bigger. As Cambridge historian Gillian Evans put it:

“Where first he had been aware of (evil’s) perverseness and emptiness, its huge darkness, its hopeless entangled knottiness, now at last perhaps he had come to feel its essential triviality in comparison with the light and power of the Good.”

In the coming weeks, here on Seen and Unseen, we will be asking some of our regular contributors to write on each of the Seven Deadly Sins, analysing how they work their deadly poison, both in the past and in contemporary society. Keep an eye out for each article as they come – it might just be the spiritual health check you need.