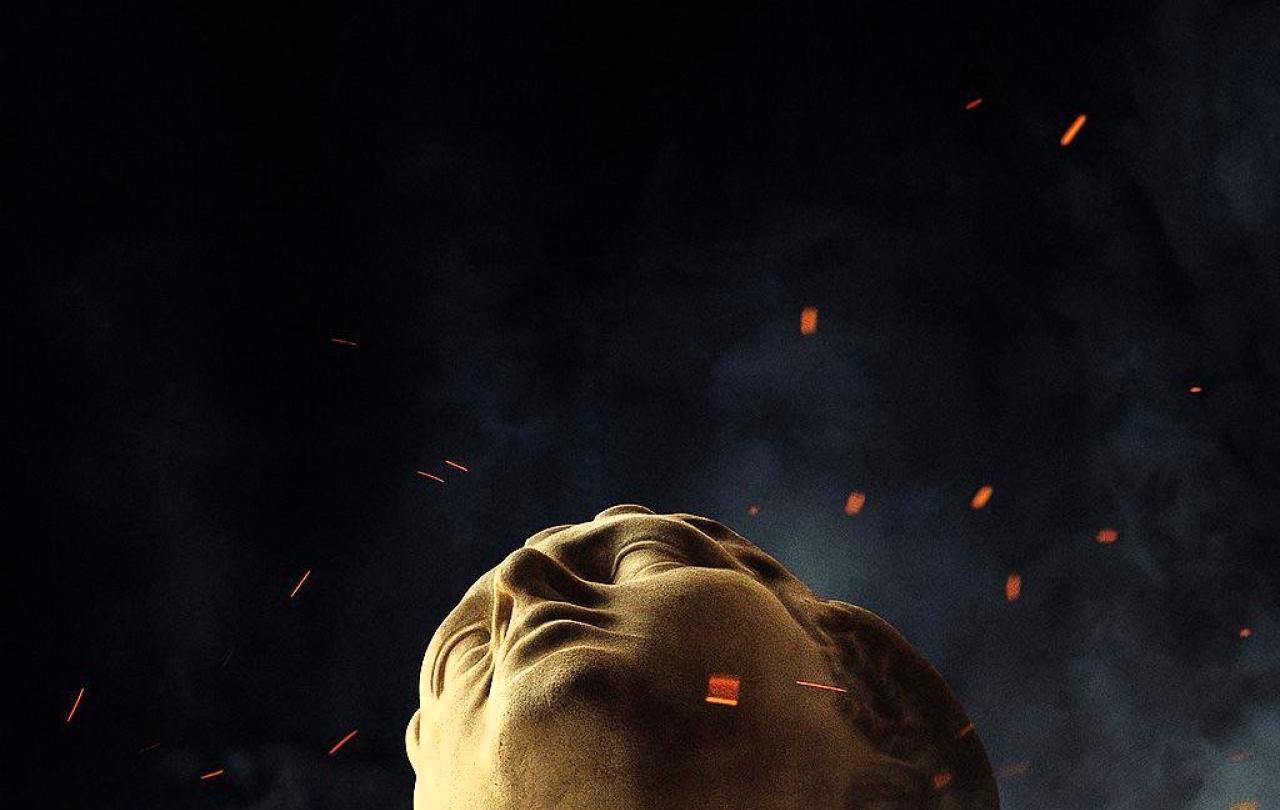

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, starring Jeremy Allen-White as the titular rock star, follows Bruce Springsteen's attempt to make possibly his most unconventional album, Nebraska. This also happened to be one of the most difficult times of Springsteen's life, battling with mental health. Before the film's release, let's briefly explore some of the root causes of Bruce's depression, and find out what part family and the church had to do with it.

When it comes to Springsteen's discography, there's something of a disconnect between the casual fans' favourite and the album favoured by critics. Born in the USA is the monster hit album, with its era defining hits and blue-collar Americana. But Nebraska is the one that musicians and writers wax lyrical about. Written and recorded in a small bedroom in Colt's Neck, New Jersey, Nebraska is an album filled with acoustic melancholy folk tracks. With no conceivable singles and no chance of getting radio play, this was not the album that Columbia records wanted him to make, but it's the album Bruce felt he had to make.

"Nebraska was the pulling back of the bow, and Born in the U.S.A. was the arrow's release" writes Warren Zanes in his 2023 book, Deliver Me From Nowhere. In it, Zanes tracks with loving detail not only the technical problems of turning recordings that were only meant to be demos into songs that you could feasibly release, but also the mental health struggles that had driven Bruce to focus on such dark subject matter. It marked a moment of the artist unpacking his issues and answering the question: what do you do when you realise that the things you've loved most have begun to do you harm?

That harm can be traced back to Springsteen's early life in 1950s New Jersey. His father, Douglas 'Dutch' Springsteen, also suffered from mental health problems, at a time when there wasn't even the vernacular to describe such things. Dutch would grow to become jealous of the attention that his young son would get from the women in his family, which would exacerbate his existing paranoia. As well as being neglectful and demeaning, Dutch would also become violent towards his son. Springsteen describes in his autobiography how on one occasion, his father was teaching him how to box when Dutch threw a few open palm punches to his face that landed just a little too hard. "I wasn't hurt" Bruce writes "but a line had been crossed. I knew something was being communicated. […] I was an intruder, a stranger, a competitor in our home and a fearful disappointment". If this was young Bruce's experience at home, little respite was found in the outside world.

Springsteen grew up quite literally in the shadow of the Catholic church, and it permeated every aspect of his community. Bruce attended a Catholic school, where on one occasion he was hit by another student as a punishment from one of his teachers. This was compounded during his time as an altar boy, when the priest he was serving at a six am service gave him a public thrashing for not knowing his Latin. So before Springsteen started high school, he had been physically abused by his father, his school, and his religion. When these pillars of his life (who were meant to represent God to him) treated him this way, is it any wonder that young Bruce's take away from all this is that God is not a safe person to be around?

Years later, when Springsteen finally takes a break from the constant recording and touring cycle, he has no way to escape the damage done to him by the experiences of his early life. In Nebraska he illustrates the lives of down and outs, blue collar workers striving to get by, and even serial killers. The subject matter was so dark that when his manager Martin Landau first heard it, he started to worry about Springsteen's mental health. Thankfully, Springsteen would get the help he needed and forty years later, is a terrific example of someone who has done the work of tackling their own issues.

Where Bruce has landed on his relationship with God some forty years later is still quite hard to pin down. He's reluctantly adopted the adage of 'once a Catholic, always a Catholic' even if he admits he doesn't participate in his religion all too often.

There's no clear delineation point between him going from being a non-believer to a believer or vice versa, but that has not stopped him from creating some truly magnificent art with intense Christian themes. References to Jesus and the gospels pepper much of his musical output. Songs like Devils and Dust show the conflicted faith of a soldier in Iraq, whilst his song, The Rising, written in response to the terrifying events of September 11th, re-imagines the firefighters climbing the stairs of the twin towers as souls rising up to meet their maker. The finished product is a compelling anthem that would give even the most heartfelt worship song a run for its money.

It's quite possible that Bruce is interested in Christianity only in as much as it is woven into the thread of American life. How much the upcoming film will focus on his relationship with God or lack thereof is unknown, but the influence the church has had on him, for better or for worse, is undeniable.

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief